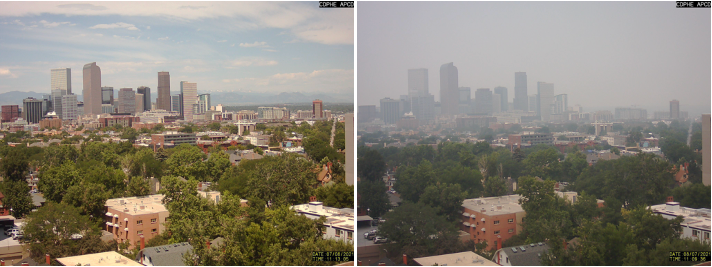

The summer of 2021 was a smoky one for Denver and northeastern Colorado.

Smoky haze from wildfires in Arizona, California, and the Pacific Northwest shrouded the Front Range mountains and cast a gray pallor over the sky on a near-daily basis. The typical pattern of monsoon-driven summer thunderstorms that normally flush out stagnant air in July and August largely failed to materialize, allowing smog cooked under the summer sun in 90-degree heat to pool along the base of the foothills to the west.

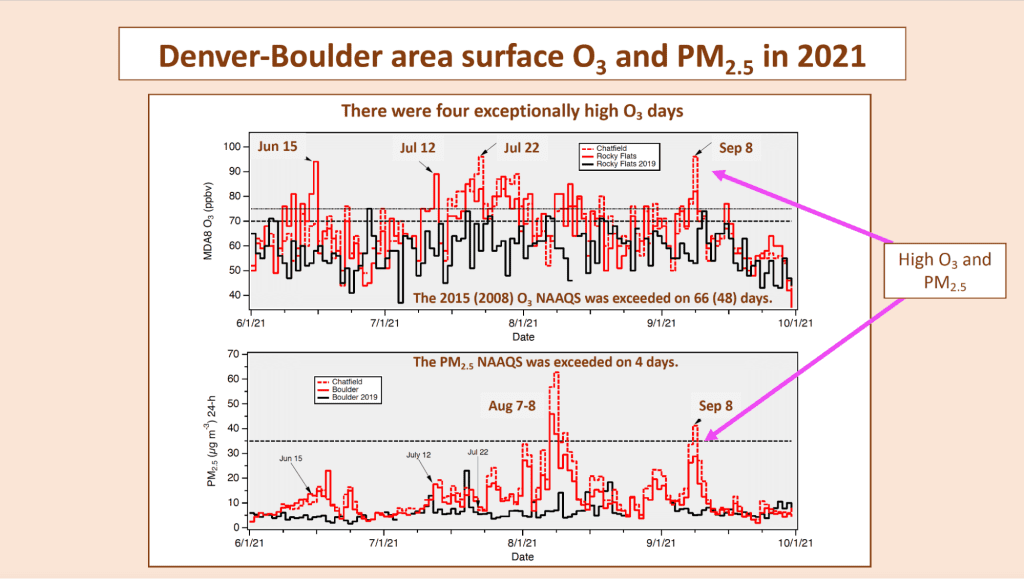

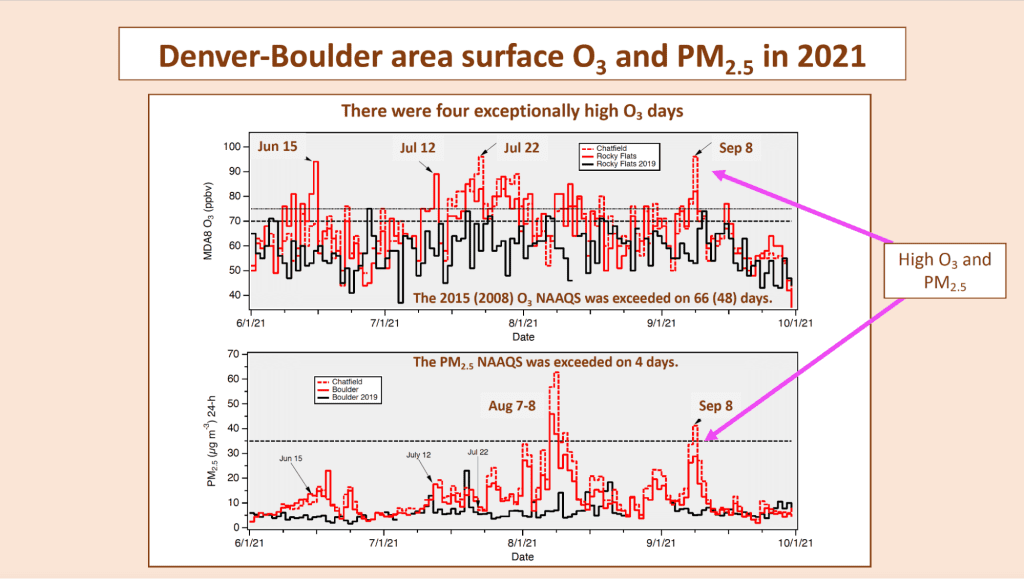

All that added up to a record number of days when ground-level ozone, which has long bedeviled the “Queen City of the Plains,” exceeded the 2015 National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) of 70 parts per billion averaged over 8 hours set by the US Environmental Protection Agency. In 2022, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed to downgrade the northern Front Range from a “serious” to “severe” violator of the 2008 federal ozone standard.

So how bad was it?

“The smoke was unpleasant to be sure,” said Andrew Langford, a research chemist with NOAA’s Chemical Sciences Laboratory, and lead author of a paper published today in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. ”Particulates, which you can see, only exceeded the air quality standard a few times that summer. Ozone exceeded the standard on more than half the days. But you can’t see ozone, so this was a much more insidious problem.”

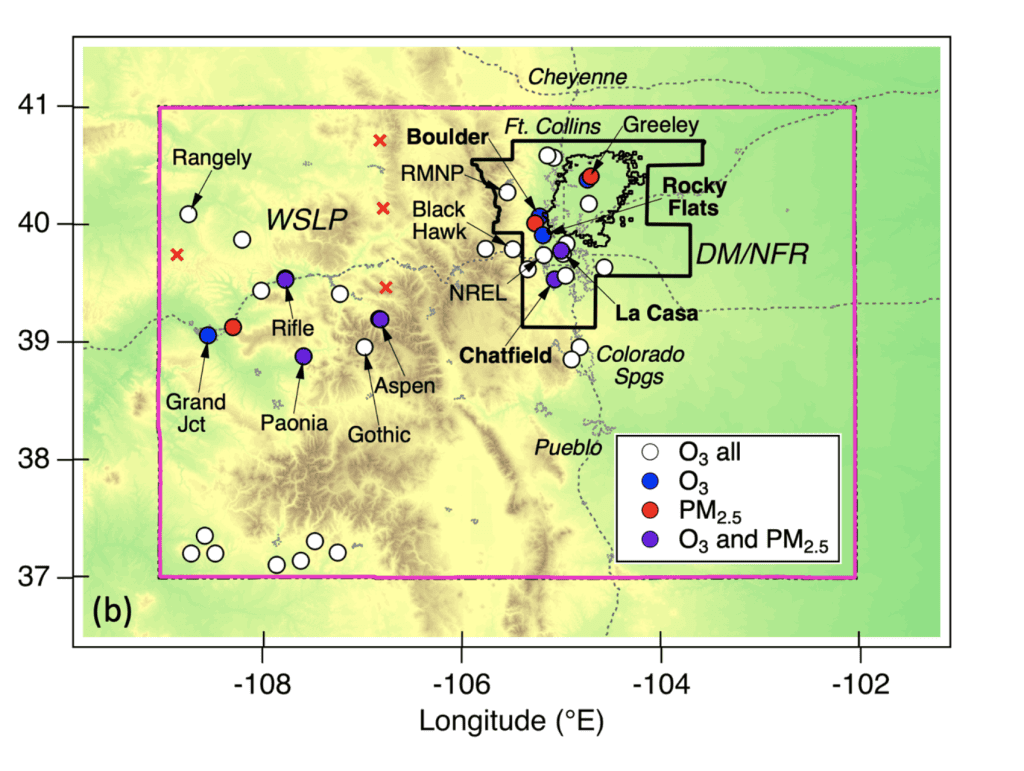

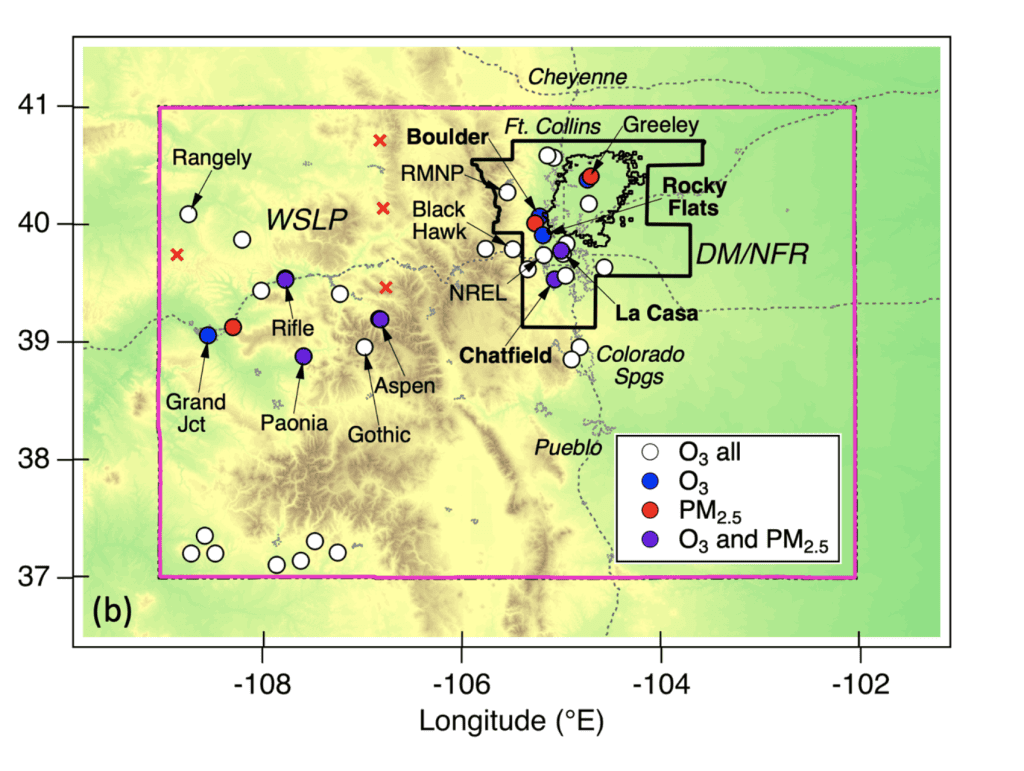

In 2021, exceedances were recorded at one or more of the 16 Northern Front Range monitors operated by the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment (CDPHE) on 66 of the 122 days from June 1 to September 30. In July, the Rocky Flats monitor operated by the state health department just west of Denver, exceeded the 8-hour standard on 22 of the 31 days.

“We estimate that without the extra ozone in the smoke, the Rocky Flats Monitor would have exceeded the standard on only 10 of those days,” Langford said.

Wildfires generate large quantities of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and fine particulates (PM 2.5), and a variety of other gaseous compounds, including reactive nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – which are the photochemical precursors of ozone. These compounds quickly react to form ozone in the fire plume and can be transported far downwind with the smoke.

Ozone and PM 2.5 both impair lung and cardiovascular function. Recent studies suggest that exposure to wildfire smoke containing both ozone and PM 2.5 can have more severe health impacts than exposure to either pollutant alone.

With a team made up of colleagues from the Chemical Sciences Laboratory, along with researchers from the NOAA’s Global Systems Laboratory and the NOAA-University of Colorado cooperative institute CIRES, Langford analyzed surface observations and upper air measurements taken in 2021 with a sensitive Light Detection and Ranging instrument, or LIDAR, to detect the smoke aloft and estimate how much ozone was in the wildfire smoke. The ozone lidar at CSL is one of only six in the entire U.S., and the only one that can measure ozone all the way from the surface to 8 km (about 5 miles).

Analysis found that maximum daily 8-hour average ozone concentrations were 6 to 8 ppb higher than in 2019, 2020, or 2022. Lidar measurements showed the extra ozone imported with the wildfire smoke to be as large as 12 ppb on some days.

That might not seem like a lot, but it represents a serious challenge for the Intermountain West, where many of the large metro areas regularly flirt with NAAQS violations even without wildfire smoke. For example, on July 12, smoke caused increased ozone concentrations in both rural and urban areas, Langford said, but it only caused exceedances in Denver, Salt Lake City, Utah, Boise, Idaho, and the Cheyenne-Laramie area of southern Wyoming–metro areas that already had elevated ozone from local pollution.

These cities are not alone. Some 200 US counties are in non-attainment with the EPA’s current ozone standard, and the agency is currently deciding whether to tighten it even further.

“You can think of transported ozone in wildfire smoke kind of like the tide,” Langford said. “Both the little ships and the big ships in the harbor will rise as the tide comes in, but now the big ships won’t be able to pass under the bridge.”

Langford said the likelihood of more smoke in more places highlights the need for effective public health communication. “People can see smoke but not ozone,” he said. “There may be days when it doesn’t look too smoky, but there’s a lot of ozone.”

He added that the prospect of more smoke arriving on the wind should also encourage air quality managers to keep the focus on cleaning up air in local areas. “It will be more and more important to reduce the sources of ozone that we have some control over,” Langford said.

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications: theo.stein@noaa.gov.