A new NOAA-funded study has documented for the first time that ocean acidification along the US Pacific Northwest coast is impacting the shells and sensory organs of some young Dungeness crab, a prized crustacean that supports the most valuable fishery on the West Coast.

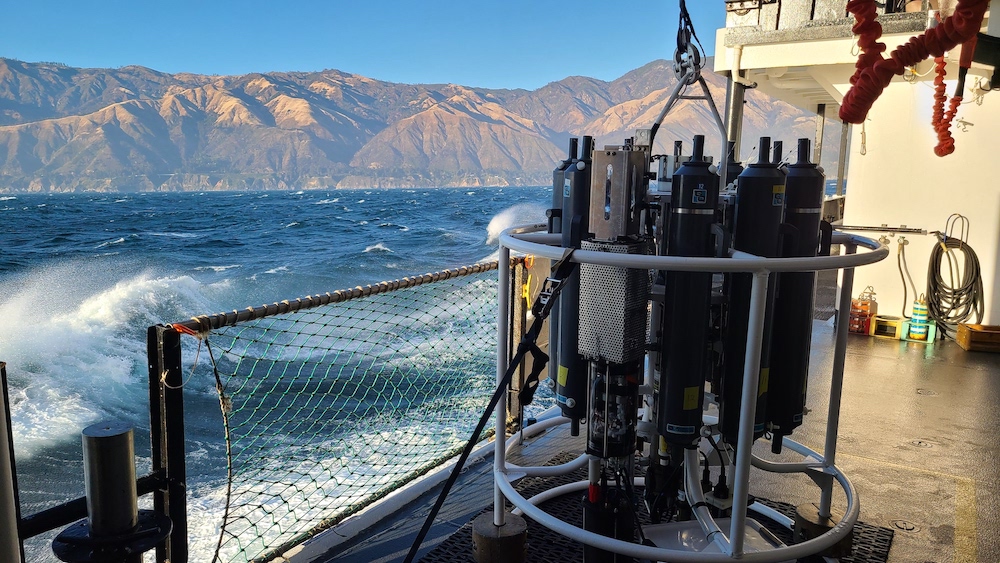

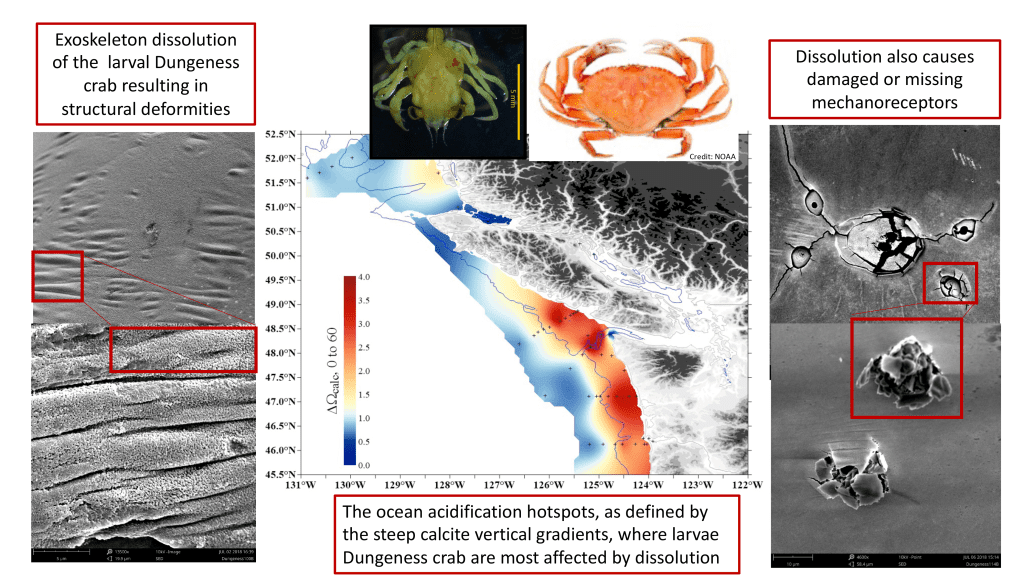

Analysis of samples collected during a 2016 NOAA research cruise identified examples of damage to the carapace, or upper shell, of numerous larval Dungeness crabs, as well as the loss of hair-like sensory structures crabs use to orient themselves to their surroundings.

The study was published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Impacts to wild crab mirror results of laboratory study

Prior to this study, scientists thought that Dungeness crab were not vulnerable to current levels of ocean acidification, although a laboratory study conducted on Dungeness crab larvae by NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in 2016 found that their development and survival suffered under pH levels expected in the future.

“This is the first study that demonstrates that larval crabs are already affected by ocean acidification in the natural environment, and builds on previous understanding of ocean acidification impacts on pteropods,” said lead author Nina Bednarsek, senior scientist with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project. “If the crabs are affected already, we really need to make sure we start to pay much more attention to various components of the food chain before it is too late.”

What is ocean acidification?

Ocean acidification refers to a reduction in the pH of ocean water, primarily caused by the uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere over long time spans. When CO2 is absorbed by seawater, a series of chemical reactions occur resulting in the increased concentration of hydrogen ions. This increase causes the seawater to increase its acidity and causes carbonate ions to be less abundant.

Carbonate ions are an important building block of structures such as sea shells and coral skeletons that rely on using calcium carbonate for structural growth. Decreases in carbonate ions can make building and maintaining shells and other calcium carbonate structures difficult for calcifying organisms such as oysters, clams, sea urchins, crabs, corals, and some kinds of shelled plankton, such as pteropods.

Close examination reveals patterns of damage

In this study, examination under a high-magnification, scanning electron microscope revealed that the corrosive conditions of coastal waters had affected portions of the fragile, still-developing external shell and legs of the tiny, almost translucent post-larval Dungeness crabs, leaving tell-tale features, such as abnormal ridging structures and scarred surfaces. This could, in turn, impair larval survival by altering swimming behaviors and competence, including the ability to regulate buoyancy, maintain vertical position, and avoid predators.

One of the more important findings of this study was that crabs showing signs of carapace dissolution were smaller than other larvae. This was disconcerting, scientists said, because the damage during the crab’s larval stages could cause potential developmental delays that could increase energy demands and interfere with maturation.

Sensory organ damage seen for the first time

In a surprising discovery, the team found that the low pH water in some coastal areas damaged the canals where hair-like bristles called mechanoreceptors stick out from the shell. These receptors transmit important chemical and mechanical sensations to the crab, and may help crabs navigate their environment. Examination showed that carapace dissolution destabilizes the attachment of the mechanoreceptor anchor, resulting in them falling out in some individuals.

This is a new aspect of crustacean sensitivity to ocean acidification that has not been previously reported. The team hypothesize that the absence or damage of mechanoreceptors within their neuritic canals may in part explain potential aberrant behavioral patterns, such as slower movement, less tactile recognition, and prolonged searching time, as well as impaired swimming, that have been observed in various crustacean species exposed to low pH conditions in laboratory settings.

“We found dissolution impacts to the crab larvae that were not expected to occur until much later in this century,” said Richard Feely, Senior Scientist with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and one of the co-authors of the study.

Combining observations and modelling work, the research team, which included scientists from JISAO, NOAA’s cooperative institute at the University of Washington, from the University of Connecticut, and from Quebec, Britain and Slovenia, demonstrated that the impacts of dissolution were the most severe in the coastal habitats, where crabs grow and mature.

Previous research has indicated that Dungeness crab may also be vulnerable to future declines due to lack of availability of prey – including bivalves such as clams and other bottom-dwelling invertebrate species.

More research needed

Bednarsek emphasized that more research will be needed to determine whether the external dissolution seen in crabs at this early life stage could carry over into later life stages, including the reproductively active adult stage, and what the potential consequences may be for the population dynamics.

“If these larval crab need to divert energy to repair their exoskeletons, and are smaller as a result, the percentage that make it to adulthood will be at best variable, and likely go down in the long-term,” she said.

Ocean acidification is a major concern for West Coast fishery managers, said Rich Childers, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s ocean acidification policy lead. “These data and results give state and tribal fishery managers and policy makers information that’s vital for harvest and conservation planning.”

The research was supported by the NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program and NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

Learn more:

Tiny shells reveal ocean waters off California are acidifying twice as fast as global ocean

Now This: What is ocean acidification?

For more information, contact Theo Stein at NOAA Communications: theoestein@noaa.gov