In honor of Women’s History Month, NOAA scientists from across the country are taking readers inside what a typical day in their life looks like. Today’s story comes from Emily Osborne, UCAR visiting scientist at the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program.

Every day at NOAA Research Headquarters in Silver Spring, MD is a little bit different. Some days are packed with meetings, some are quiet and full of reading and writing, and others are spent in the field or traveling to conferences. No matter the specific day, one thing is for certain: my proudest moments at NOAA have been represented by a culmination of hard work and time.

I have been working at NOAA since 2017, and for the past year have been working as a visiting scientist with NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program. One of my main responsibilities is to lead the process for visioning and drafting of the agency-wide research plan that details the most urgently needed ocean acidification science for the coming decade. This type of work — supporting, guiding, and promoting ocean research at the federal level — is why I chose to leave the academic sector in 2016 after completing my PhD.

While I currently fill a management role at NOAA, I still identify as a “scientist” and have made it a priority to publish my own original research. This past December, I had the privilege of seeing my research published in the high-impact journal Nature Geoscience.

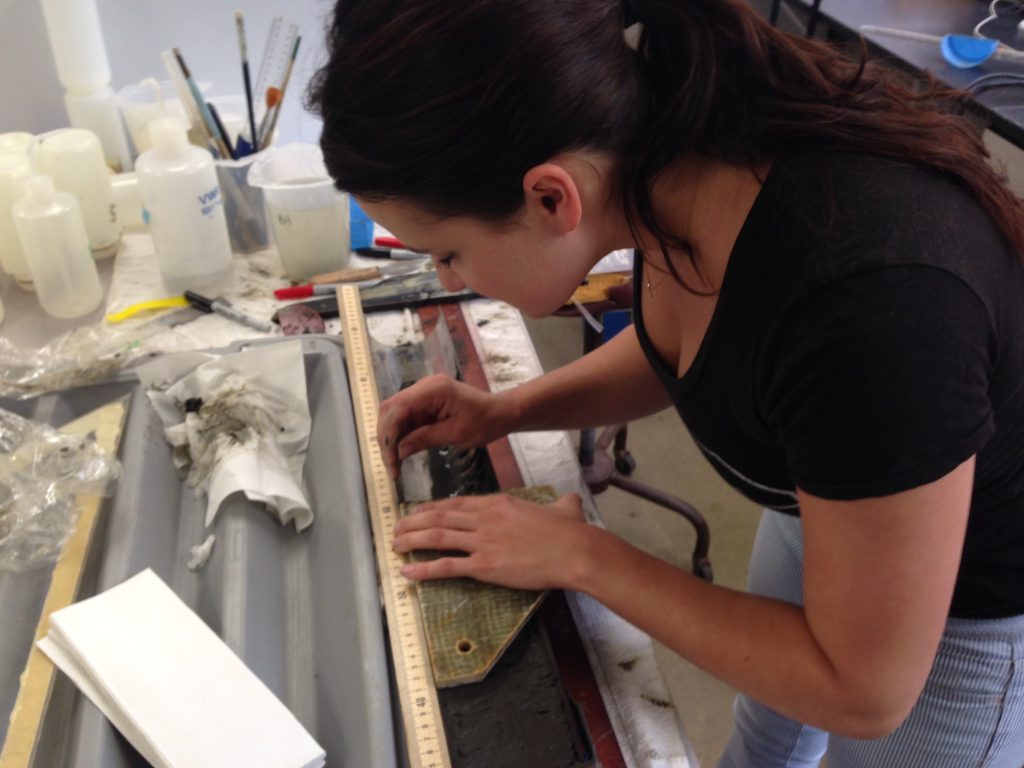

This publication included research that I began as a graduate student at the University of South Carolina in 2012 in partnership with NOAA Ocean Acidification Program scientists. That’s right, it took me seven years from conceptualization to publication. For this particular project, I looked at tiny fossil shells (no larger than a grain of sand) preserved on the seafloor to get an idea of how ocean chemistry changed over the past 100 years (a period of time in which we have a severe lack of direct observations). This work, based off of the coast of California, revealed that over the last century, ocean acidification has been occuring twice as fast in this coastal region relative to the global ocean average.

The results of this study were published in 55 news outlets, including on the front pages of the Los Angeles Times and New York Times, and tweeted about by more than 130 members of the public, scientists, and communicators (journalists, bloggers, editors). The Los Angeles Times article also caught the attention of California Senior Senator Dianne Feinstein, who invited me to her Capitol Hill office to brief her staff on ocean acidification and plans for resilience along the California coast. Following my visit, Senator Feinstein crafted a press release and letter to Department of Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross that included the newly published results of my work. All within the course of a week, I got to see my thousands of hours spent behind a microscope transition into both an increased public understanding and awareness of ocean acidification as well as a positive impact on public policy.

Moments like these and the opportunity to work on projects that can create positive change are the reasons I work at NOAA. As an early-career female scientist, I also ground some of my success in finding and building a supportive and inspiring network of colleagues and mentors, which has grown vastly during my time here at NOAA.