Airborne mission finds a global belt of particle formation is making clouds brighter

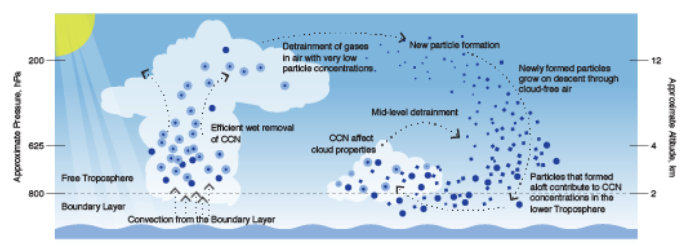

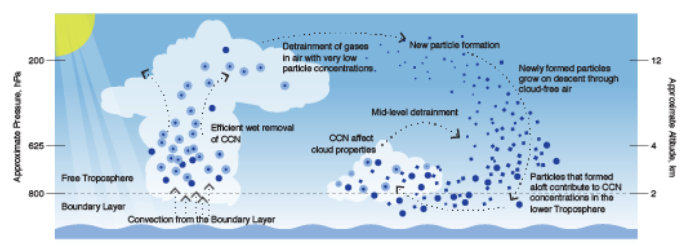

When clouds loft tropical air masses high into the sky, some of the gases they carry can be transformed into tiny particles, initiating a process that that may end up brightening lower-level clouds and reflecting more sunlight away from Earth. Exactly how much sunlight these clouds reflect has always been a question because of the large, unsampled expanses of atmosphere over the tropical oceans.

Now, in one of the first studies published from the largest and longest airborne chemistry research campaigns ever attempted, a CIRES scientist working at NOAA estimates that this cloud-brightening process could occur over 40 percent of the Earth’s surface – a significant number that calls into question whether climate models are accurately representing clouds’ cooling effect.

The study was published October 16 in the journal Nature.

“Understanding how these particles form and contribute to cloud properties in the tropics will help us better represent clouds in climate models and improve those models,” said lead author Christina Williamson, a CIRES scientist working at NOAA.

Williamson was one of dozens of scientists who participated in the Atmospheric Tomography Mission, an unprecedented campaign to sample the atmosphere over the middle of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in NASA’s DC-8 flying laboratory. Over three years, teams of scientists in the DC-8 flew from the wavetops to the high atmosphere, traversing open ocean from pole to pole, collecting chemical observations all the while.

The researchers found that gases transported to high altitudes by deep convective clouds in the tropics formed large numbers of very small aerosol particles, a process called gas-to-particle conversion.

Outside the clouds, the air descended toward the surface and those particles grew as gases condensed onto some particles, while others stuck together to form larger particles. Eventually, some of the particles grew large enough to influence cloud properties in the lower troposphere.

In their study, the researchers showed that these particles brightened tropical clouds. “That’s important since brighter clouds reflect more energy from the sun back to space,” Williamson said.

The team observed this particle formation in the tropics over both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, and their models suggest a global-scale band of new particle formation covering about 40 percent of the Earth’s surface.

In places with cleaner air where fewer particles exist from other sources, the effect of aerosol particle formation on clouds is larger. “And we measured in more remote, cleaner locations during the ATom field campaign,” Williamson said.

Exactly how aerosols and clouds affect radiation is a big source of uncertainty in climate models. “We want to properly represent clouds in climate models,” said Williamson. “Observations like the ones in this study will help us better constrain aerosols and clouds in our models and can direct model improvements.”