One key to the past is crowd-sourcing data recovery

It’s been the stuff of science fiction for generations: a time machine that would allow researchers to reach back into yesteryear and ask new questions about long-ago events.

This month, a NOAA-funded research team published an update to a weather “time machine” they’ve been developing since 2011. This third version of the 20th Century Reanalysis Project, or 20CRv3 for short, is a dauntingly complex, high-resolution, four-dimensional reconstruction of the global climate that estimates what the weather was for every day back to 1836.

The newest update provides continuous estimates of the most likely state of the global atmosphere’s weather on 75-kilometer grids eight times a day for the past 180 years. It’s the scientific fruit of an international effort led by researchers with NOAA’s Physical Sciences Division (PSD) and CIRES and supported by the Department of Energy.

The research opportunities that this work makes available are almost boundless, said Gil Compo, a CIRES scientist working at NOAA who leads the reanalysis project. “We’re throwing open the door to lost history, and inviting scientists to pour through,” Compo said.

Old weather records fed into modern weather model

Using NOAA’s Global Forecast System, researchers reconstructed the global atmosphere from surface pressure readings, sea temperature and sea ice observations from archival records, some transcribed by citizen volunteers. From this data, the model estimates temperature, pressure, winds, moisture, solar radiation and clouds.

This painting by James Gale Tyler depicts the crew of the USS Jeanette abandoning ship in 1881 after more than a year trapped in Arctic ice. Barometric pressure observations from the ship’s log comprise some of the data used to reconstruct global weather in the updated 20th Century Reanalysis dataset released by NOAA on Oct 9, 2019. Source: Wikipedia

Scientists have used previous 20th Century Reanalysis datasets as a foundation for a wide range of studies, from understanding large-scale climate trends to diagnosing the impacts of individual historical extreme weather events. The dataset allows researchers to explore how climate change is influencing temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric circulation, and compare today’s storms, heat waves, droughts and floods to historic events.

“This tool lets us quantitatively compare today’s storms, floods, blizzards, heat waves and droughts to those of the past and figure out whether or not climate change is having an effect,” Compo said. “This should be useful for climate attribution research.”

Enriching our understanding of long-ago events

Scientists have also used the previous versions of the “old weather” data to discover unknown hurricanes, study the climate impact of old volcanic eruptions, investigate the timing of bird migrations, and even explore the economic impact of diseases spread by the tsetse fly in sub-Saharan Africa.

Colorado State University hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach said he can’t wait to begin working with 20CRv3. “I’m a huge fan of reanalysis products,” said Klotzbach. “I’ll probably be diving in by next week and I know my colleagues are looking forward to working with it.”

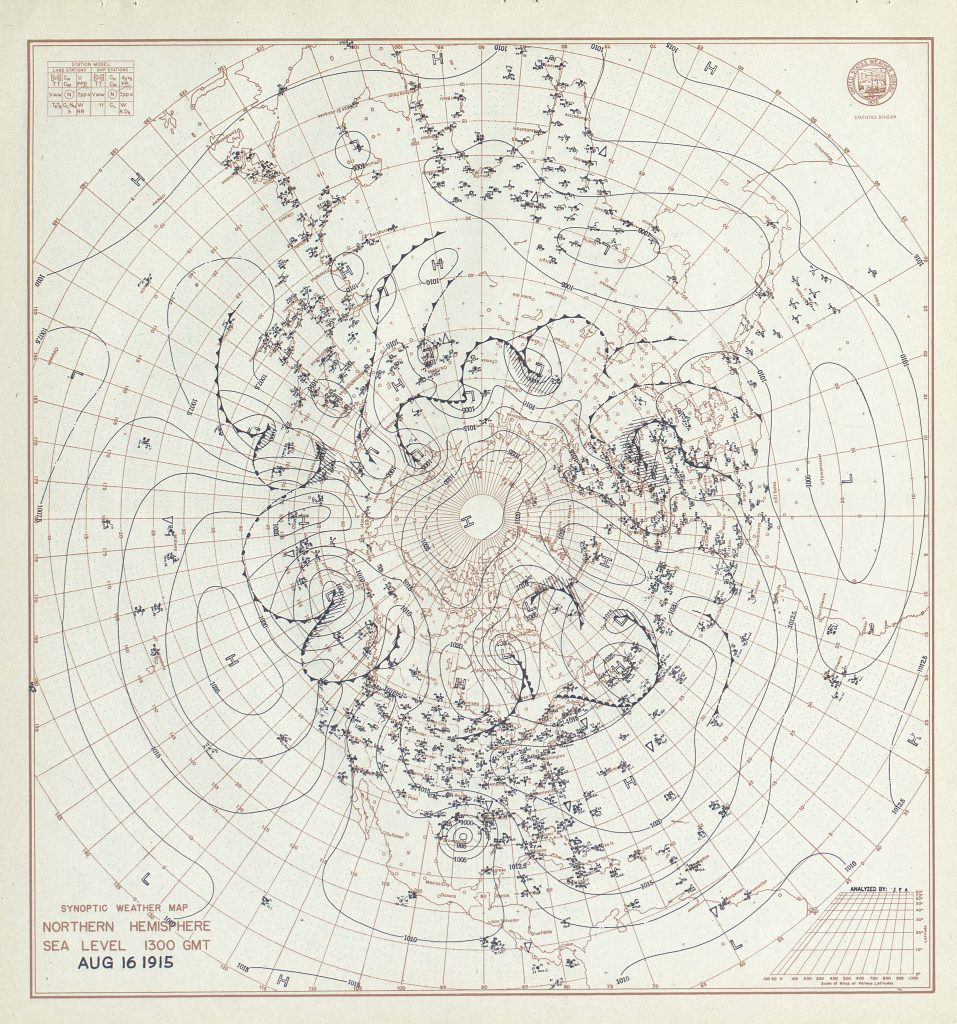

This U.S. Weather Bureau Map depicts northern hemisphere circulation patterns on Aug. 16, 1915, as the Galveston hurricane made landfall on the Texas coast. Surface pressure observations from historic weather records like this allow scientists to reconstruct global weather using modern weather models. Credit: NOAA Physical Sciences Division

Others have used the data to enrich the scientific understanding of specific weather lodged in cultural memory, like the sinking of the Titanic or the extraordinary winter of 1880-1881, which was chronicled by Laura Ingalls Wilder in her book “The Long Winter.”

“I’ve found reanalysis composites incredibly useful and accessible,” said Barbara Mayes Boustead, a meteorologist instructor with NOAA’s National Weather Service, who has studied the winter of 1880-1881. “We introduce them in our course on operational climate services and to weather forecast offices who want to investigate climate events like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation.”

A big appetite for big data

20CRv3 uses millions more observations than previous versions of the reanalysis, especially for earlier periods. The new reanalysis includes up to 25 percent more available observations for years prior to 1930. Running the model and crunching all this data required astronomical computing resources. To accomplish this third upgrade, the Department of Energy donated 600 million cpu hours to crunch 21 million gigabytes of data at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center.

The result? This new update provides a much better indication of where the weather estimates are more reliable, and where more observations are needed.

“The atmospheric estimates from 20CRv3, as well as their uncertainties, are much more reliable than those from the previous reanalysis, particularly in the 19th century,” said Laura Slivinski, a CIRES meteorologist and the lead author of a recent paper in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society that lays out improvements in their reanalysis techniques. “We’re more certain about how much we know, and where we need to know more.”

Citizen scientists help chart a “virtuous circle” of discovery

Some of the key players in the reanalysis story are groups like Atmospheric Circulation Reconstructions over the Earth, which marshals professional scientists and ordinary citizens alike to pore over historical documents like ship logs and extract meteorological observations that are used to refine old weather reconstructions. Targeted data rescue can be extraordinarily valuable – for example, logs of 19th Century wooden sailing vessels attempting to penetrate the Arctic and Antarctic.

“These data have been invaluable to us because they come from the otherwise data-sparse polar regions,” Slivinski said.

“20CRv3 also provides a literal map to further advances in precision by identifying regions and time periods where additional weather observations will improve model estimates,” she added.

Earlier time periods, especially in the Southern hemisphere, still have high uncertainty. Luckily, data rescue can help fix that. “This dataset can keep getting better as we unlock more observations from historical archives,” Compo said. “It’s really a virtuous circle.”

The 20th Century Reanalysis Project version 3 dataset received support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research and NOAA’s Climate Program Office.

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications, at theo.stein@noaa.gov.

To learn more about participating in data recovery, visit https://www.oldweather.org.