Robot’s epic voyage provides clues

When an uncrewed, instrumented robot circumnavigated Antarctica during the winter of 2019, it marked a technological triumph over some of the fiercest marine conditions on Earth. Now, analysis of direct measurements collected during this epic voyage are highlighting questions about the vast circumpolar ocean’s role in storing carbon dioxide.

The findings were published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Covering only 30 percent of Earth’s ocean surface, the Southern Ocean plays an outsized role in the global climate. It is the meeting point of ocean currents, and an important connector between the atmosphere and deep ocean for the transfer of heat and carbon. Based on measurements collected from ships over several decades, scientists concluded that the Southern Ocean is a major buffer against climate change, absorbing as much as 75 percent of the excess heat and 40 percent of human-generated carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions taken up by the global oceans.

More recently though, biogeochemical measurements taken by autonomous Argo floats between 2014 and 2017 suggest the Southern Ocean’s role as a carbon “sink” that absorbs CO2 is much smaller – perhaps barely any sink at all, said Adrienne Sutton, an oceanographer with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, who is investigating the discrepancy between ship and float data.

“If we’re wrong about the Southern Ocean being a strong sink, then where’s all that carbon dioxide going?” Sutton asked. “The answer is important for understanding how the Earth system is responding to climate change.”

Oceans are key to understanding climate change

Ocean measurements are key to understanding the global carbon cycle, and how the natural ocean and land serve as sinks for carbon and are responding to climate change driven by concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere.

The amount of CO2 absorbed or emitted by the Southern Ocean, which scientists call CO2 flux, is primarily a balance between the outgassing of natural carbon in deeper water rising to the surface that is not consumed by plankton and other biological processes, and the absorption of increasing CO2 levels in the atmosphere caused by human activity. These processes occur continuously, simultaneously and with varying intensity across the Southern Ocean from the warmer subtropical waters to the icy seas around Antarctica.

One challenge with ship-based measurements of carbon flux is that the Southern Ocean is immense, and research cruises are few and far between, especially in winter. While Argo biogeochemical floats can sample in harsh winter conditions unfit for safe ship operations, there are questions about how representative their measurements are, given their small numbers and brief sampling history. Confounding matters, calculations of how much carbon is absorbed or emitted rely on satellite-based wind and sea-level pressure estimates, which have been shown to add significant uncertainty to the results in some regions.

“Our results show direct measurements, year-round, are needed to crack open the uncertainties about how the Southern Ocean is controlling the earth’s carbon budget,’ said coauthor Bronte Tilbrook, an oceanographer with CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere in Australia. ”Right now, we have nowhere near the coverage that we need.”

Boldly going into the unknown

The voyage by the Saildrone, which covered more than 13,000 miles over 196 days, was an important test of a platform that could help close the yawning data gaps scientists currently face.

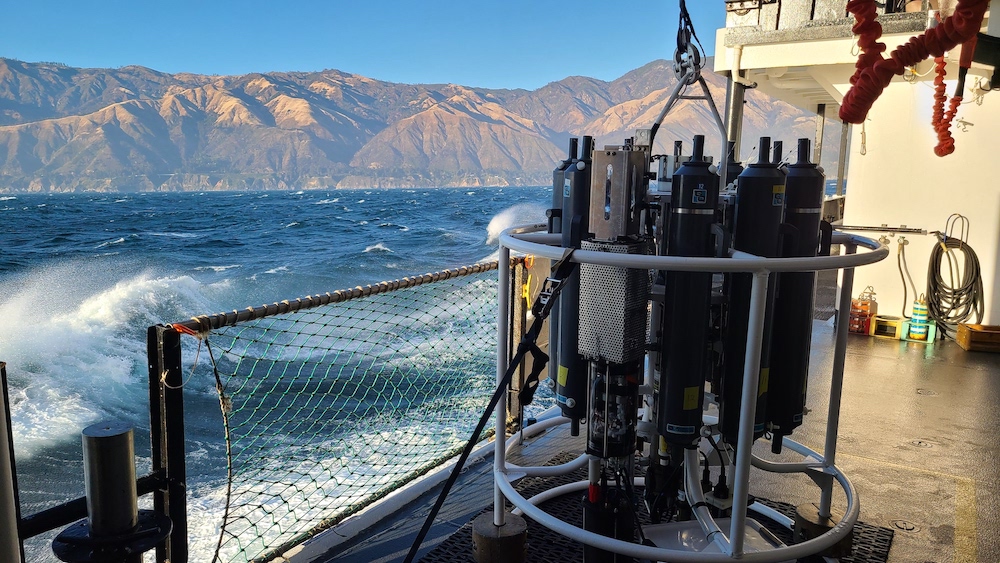

Saildrone is an Uncrewed Surface Vehicle, or USV, that can be remotely controlled to navigate a specific route while collecting data from on-board instruments and sensors. A specially modified Saildrone USV, built to survive the extreme high winds and waves of the Southern Ocean, collected measurements of wind, air pressure, and CO2 from both the sea surface and atmosphere every hour, while navigating 50-foot waves and surviving at least one collision with an iceberg.

With two counterparts – neither of which would finish the mission – Saildrone 1020 launched from Point Bluff, New Zealand on January 19, 2019, collecting and transmitting a range of data on weather, seal and krill populations, and levels of CO2, in the air and water.

By directly measuring wind speed, along with CO2 in the air and surface seawater, scientists were able to observe CO2 exchange between the ocean and atmosphere every hour during the mission. Using these data, they estimated potential errors in these measurements, as well as potential errors due to other approaches to estimating CO2 exchange.

Although data showed the ocean was both absorbing and emitting CO2 during the voyage, outgassing was prevalent during late fall and early winter in the Indian Ocean sector of the Antarctic Zone, which comprised about one third of the route.

“The outgassing we measured in 2019 was not as strong as the outgassing measured by Argo biogeochemical floats in this same region in 2014 and 2015, so we expect that CO2 flux conditions are highly variable from year to year,” Sutton said.

Some climate models show intensification of winds and acceleration of the overturning circulation in the Southern Ocean due to climate change would reduce ocean CO2 uptake. Over the next century models also predict reductions in sea-ice cover and surface ocean warming, freshening, and stratification, which are all expected to impact the carbon sink. How these processes impact the overall balance of CO2 uptake and outgassing in the Southern Ocean is uncertain.

“Arguably the best way to improve our predictions of future ocean and climate change is to better understand how the system behaves today,” said co-author Nancy Williams, assistant professor at the University of South Florida College of Marine Science. “This will require collecting more ocean carbon data from regions and seasons which have been historically undersampled, such as the Southern Ocean in winter, and using those findings to improve ocean models.”

Williams and Sutton have a proposal pending at the National Science Foundation to fund two more USVs for deployment to the Southern Ocean in winter 2022.

Funding for the Saildrone’s circumnavigation of Antarctica was provided by The Li Ka Shing Foundation. Major support for CO2 observing technology development was provided by NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program.

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications, at theo.stein@noaa.gov.