It’s been 50 years since Bill Quinn of Oregon State University and Klaus Wyrtki of the University of Hawaii made the first attempt to forecast the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). While their initial prediction was incorrect, it marked the beginning of a journey toward understanding and predicting one of the most influential climate phenomena on Earth. So, what is El Niño and why is it so important to anticipate the timing of the cycle?

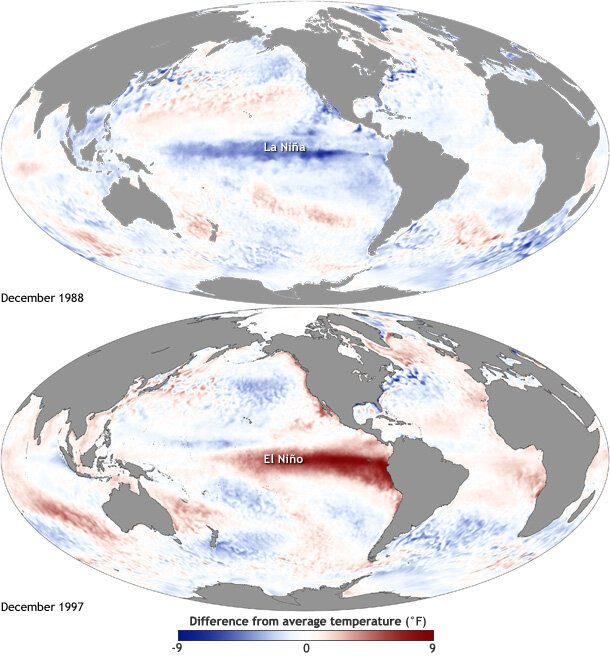

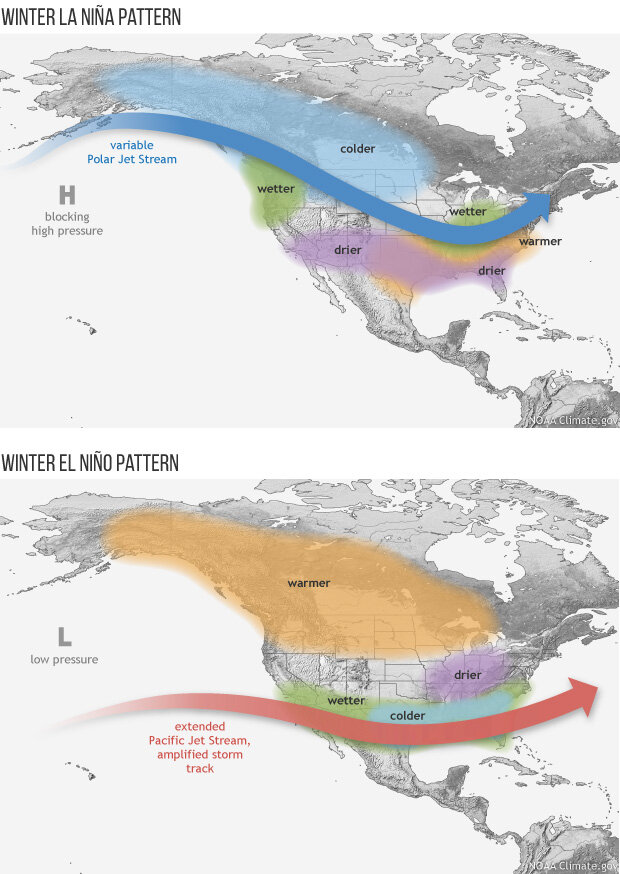

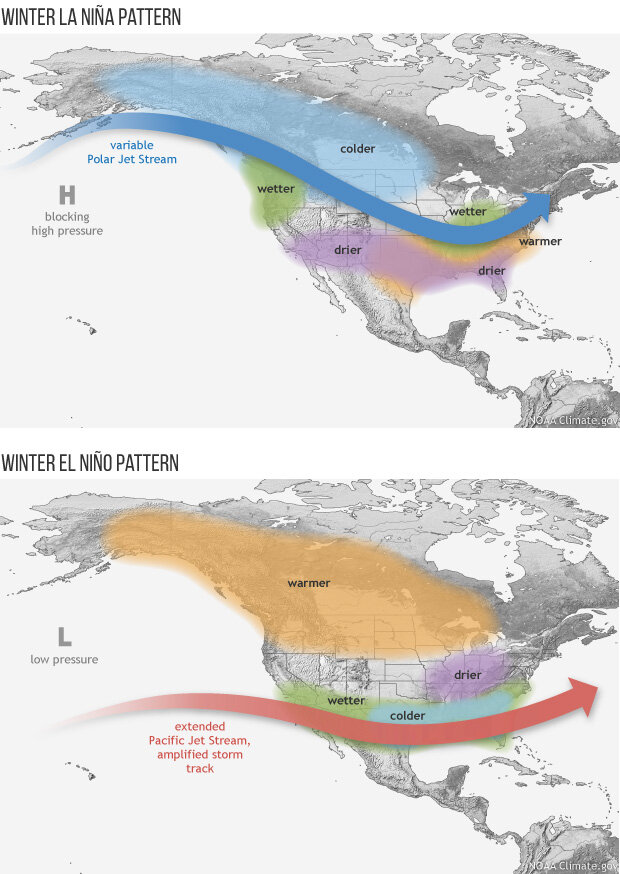

ENSO is a climate phenomenon made up of two states, or phases: “El Niño,” and “La Niña.” When the planet is not in either phase, it is said to be “ENSO-Neutral.” On average, El Niño and La Niña occur every 3-7 years and each phase lasts about 9-12 months. ENSO is a coupled climate phenomenon, so there must be changes in both the ocean and atmosphere. If only one appears to be in El Niño or La Niña, the tropical Pacific ocean is ENSO-Neutral. Each phase of ENSO has distinct impacts that reverberate globally.

In 1974, Quinn and Wyrtki were motivated to forecast ENSO by El Niño’s impacts on the Peruvian anchovy fishery, the largest commercial fishery at the time. When waters warmed and fish migrated to cooler areas, the anchovy industry collapsed and a cascade of other economic consequences followed. El Niño’s warmer sea surface temperatures (SSTs) may also cause changes in weather such as increased thunderstorm activity over the central and eastern Pacific. Meanwhile, in the Atlantic, there is an overall reduction in the frequency and strength of hurricanes due to changes in the jet stream and wind shear. ENSO has also been shown to affect tornadoes, wildfires, surf conditions, salmon populations, atmospheric rivers, coastal flooding, snowfall, and additional impacts around the world. This year, we may see a more active hurricane season, as scientists predict the onset of La Niña conditions sometime between June and August 2024.

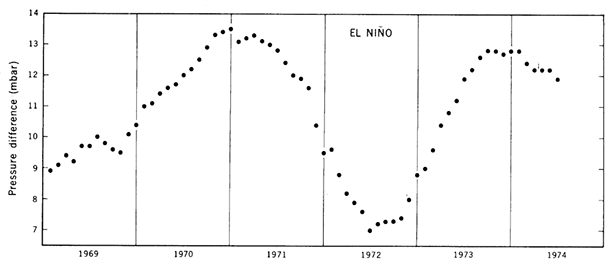

Because of ENSO’s global influence, it has been critical to improve our ability to study and predict the ENSO cycles. The first ENSO forecast relied on the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), a measure of the strength of the trade winds. Bill Quinn predicted that since the SOI was elevated in 1973 and the beginning of 1974, then rapidly decreased toward the end of the year, a weak El Niño should begin in 1975.

To test their hypothesis, Quinn and Wyrtki set out on the “El Niño Watch Expedition” in February-March and April-May 1975 to measure SSTs. During the first cruise, the researchers were excited by warm waters east of the Galapagos Islands, but unfortunately, conditions were back to normal during the second research cruise in May. Quinn and Wyrtki’s forecast was incorrect. While no El Niño developed in 1975, they were able to lay the groundwork for future advancements.

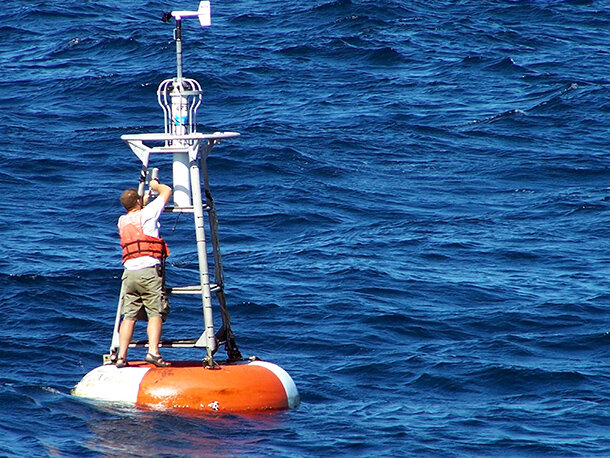

In the years since, we have developed ocean observing systems including satellites, buoys, and moorings to collect data to input into our sophisticated dynamic and statistical prediction models. Quinn and Wyrtki did not have access to data from the Tropical Atmospheric Ocean (TAO) moored buoy array across the equatorial Pacific Ocean that provides real-time data on SST, winds, relative humidity, air temperature, and water temperature at 10 depths in the upper 500 meters (1640 feet) of the ocean. All of this information can be input into our dynamic climate models where complicated processes like heat transfer, air movement, and condensation can be described by equations. Because of our advances in computing, our models have become more accurate over time. (ENSO predictions from dynamic and statistical models are available in near-real time from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society.)

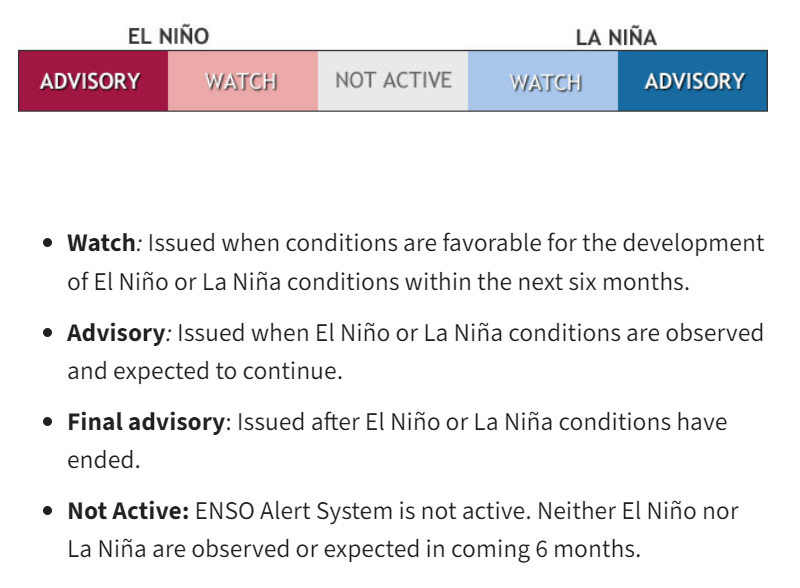

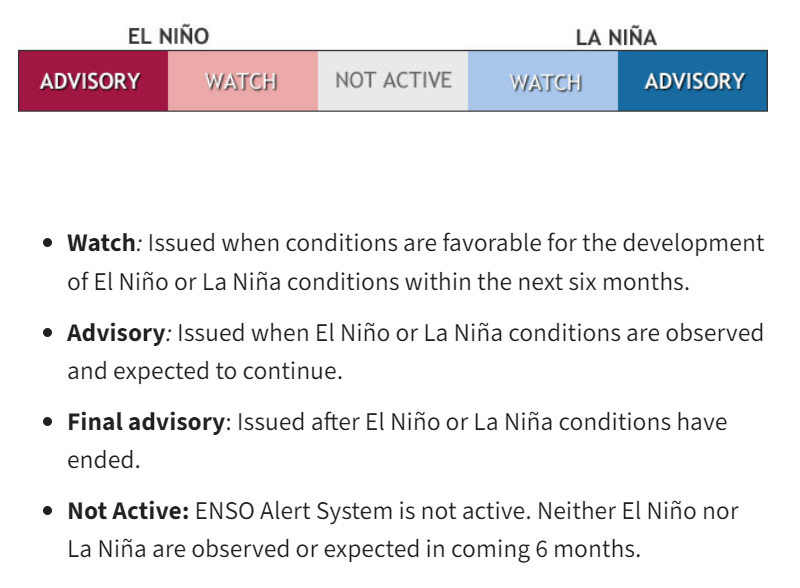

These advancements have also allowed scientists from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center to create the El Niño and La Niña Alert System, which provides the official US government ENSO status update on the second Thursday of each month. By combining real-time observations with predictive models, scientists can use the ENSO Alert System to issue warnings and advisories to communities, governments, and businesses to prepare for potential disruptions from these changes in climate and weather.

Despite these strides, ENSO prediction remains imperfect. Climate models are continually advancing, incorporating new data and refining algorithms to improve accuracy. Each year, scientists from NOAA Climate’s ENSO Blog analyze seasonal outlooks in order to learn from the patterns that emerge. Looking ahead, challenges remain. Climate is complex, and ENSO prediction is no exception. Uncertainties persist, reminding us of the need for continued research and innovation. We have come a long way from relying only on in situ observations like the SSTs Quinn and Wyrtki collected during the El Niño Watch Expedition. As we celebrate 50 years of progress, we also continue to embrace the challenges of tomorrow for improved ENSO forecasting.

Want to learn more about ENSO? Check out these articles:

- February 2024 ENSO Outlook: All along the La Niña WATCH-tower

- El Niño and La Niña: Frequently asked questions

- How will we know when an El Niño has arrived?

- Why Past ENSO Cases Aren’t the Key to Predicting the Current Case

- Team effort: the North American Multi-Model Ensemble

- No, you can’t blame it all on El Niño

- ENSO + Climate Change = Headache

- Has climate change already affected ENSO?