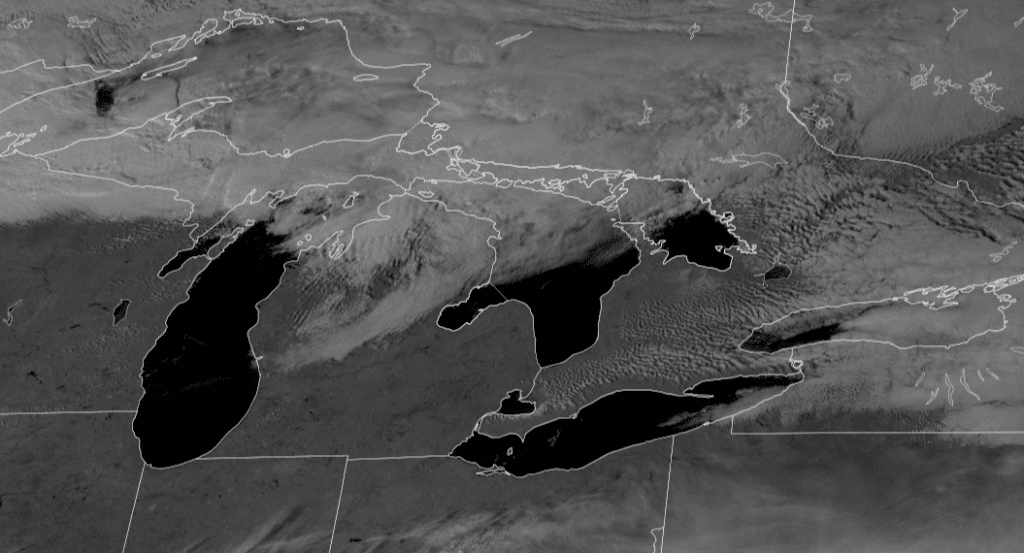

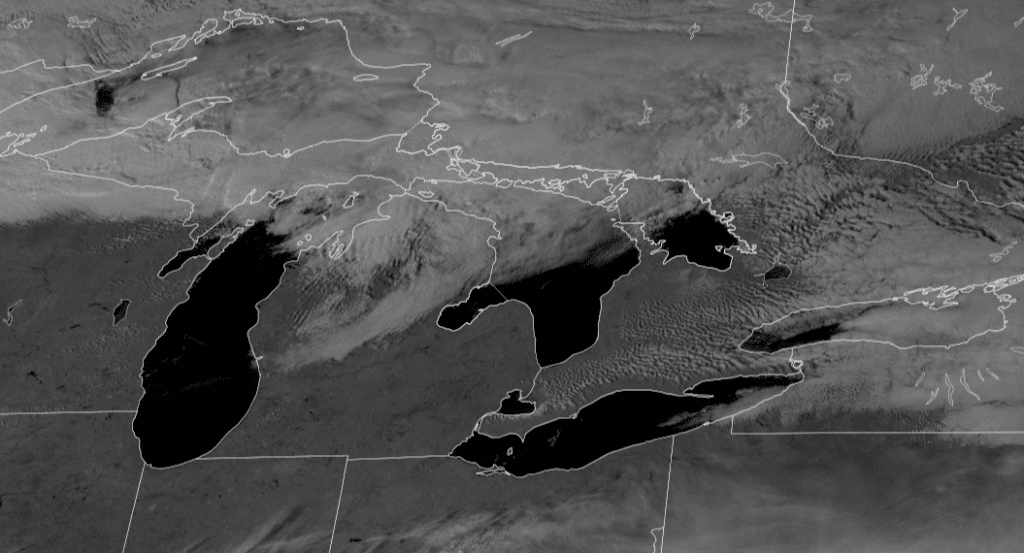

NOAA researchers at NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) report that they’ve seen a steady decrease in ice coverage across the Great Lakes, which has reached a historic low.

Together, Great Lakes ice coverage was measured at 2.7 % on February 11, 2024.

Coverage on each of the lakes was measured as follows:

Lake Superior 1.7 %

Lake Michigan 2.6 %

Lake Huron 5.9 %

Lake Erie 0.05 %

Lake Ontario 1.7 %

Lakes Erie and Ontario are basically at – or tied with – their individual historic lows for the date, making both essentially ice-free.

“We’ve crossed a threshold in which we are at a historic low for ice cover for the Great Lakes as a whole,” says GLERL’s Bryan Mroczka, a physical scientist. “We have never seen ice levels this low in Mid-February on the lakes since our records began in 1973.”

The current winter season (2023-24) began with very warm air temperatures, resulting in slow ice formation. January 2024 did see some periods of cold, but they were not sustained long enough to allow ice coverage to increase with our current year peak reaching between 15-20% coverage during the third week of January. Maximum ice cover for the year usually peaks in late February or early March and, on average, the Great Lakes experience a basin-wide maximum in annual ice coverage of about 53%. [Check out this Q&A with GLERL scientists that goes into more detail about the causes and impacts of this year’s low ice cover.]

Communities around the lakes have strong economic ties to the ice levels and the changes in ice cover can have big impacts on the people living there. Many local businesses in the area rely on ice fishing and outdoor sports which can only happen if the ice is thick and solid. Some fish species also use the ice for protection from predators during spawning season, and there’s increasing evidence that the ice plays a role in regulating many biological processes in the water. Shipping schedules are heavily impacted by the formation of ice, as well.

The absence of ice can also make the shoreline more susceptible to erosion and increase the potential for damage to coastal infrastructure during the winter months due to high winds and waves. Thick ice often acts to dampen the large wave action and protect the shoreline. Lack of ice cover can also increase lake effect snow.

In concert with the U.S. National Ice Center, NOAA obtains, produces, and delivers environmental data and products for near real-time observation of the Great Lakes to support research on ice cover changes and decision making at various levels.

The relationship between ice cover and Great Lakes water level fluctuations is complex, explains GLERL researcher Lauren Fry. “Evaporation happens when there is a large temperature difference between the air and water,” says Fry. “We tend to see the highest evaporation rates during the fall and early winter when the surface water is relatively warm and cold blasts of Arctic air enter the basin.”

People are often surprised to learn that much of the evaporation on the Great Lakes happens while ice is forming, she says. Fry compares it to the difference between the way a warm cup of hot chocolate on a cold day evaporates as steam, whereas a cold glass of ice water on a warm summer day results in condensation.

To view up-to-date information on ice, visit the Great Lakes node of Coastwatch.

Media contact: Alison Gillespie, alison.gillespie@noaa.gov, 202-713-6644.