Analyzing the forecast, decision support and new tools for the future

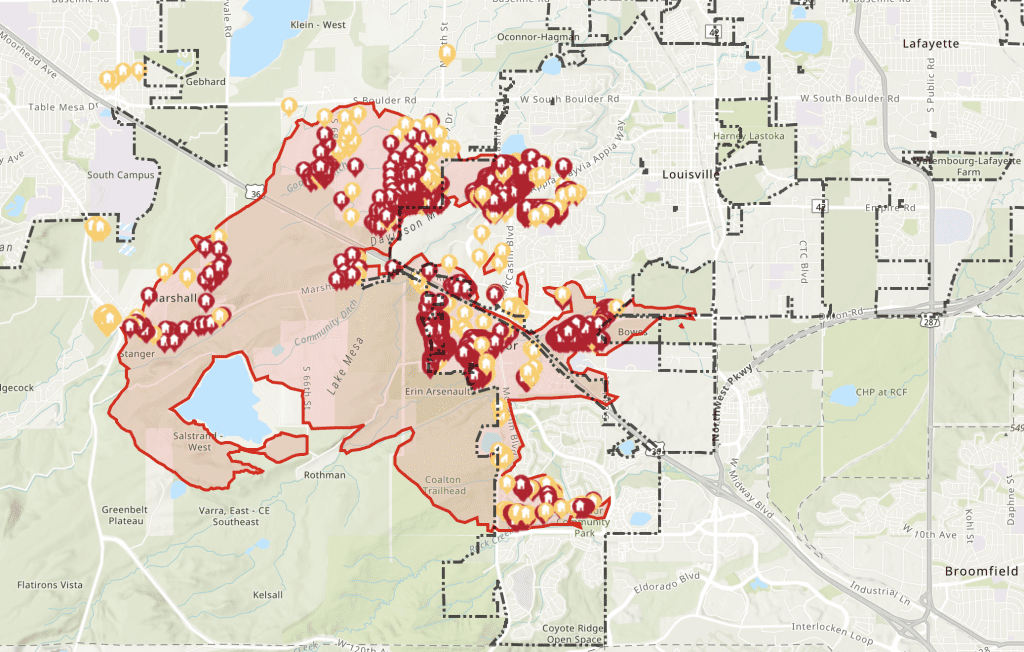

The wind-driven Marshall Fire erupted into the most costly wildfire in Colorado history on December 30, 2021, evolving in one hour from a grass fire into a suburban firestorm that destroyed 1,084 homes and seven commercial properties as it swept into the Boulder suburbs of Louisville and Superior.

In a recent analysis, NOAA scientists and meteorologists in Boulder closely examined the forecasting challenges posed by the “mountain wave” windstorm, an event that regularly occurs along the base of the Rocky Mountains, as well as the operational challenges during the firestorm that followed. Their findings appeared recently in Weather and Forecasting, a journal published by the American Meteorological Society.

During the two days before the fire, numerical weather models began to suggest high winds for December 30. But starting at 5 p.m. on December 29, one short-term model began to generate remarkably consistent run-to-run forecasts for the location and onset of the windstorm, which gave NOAA/National Weather Service (NWS) meteorologists confidence to issue a high-wind warning across the urban areas of Boulder County, said lead author Stan Benjamin, a CIRES scientist working at NOAA’s Global Systems Laboratory. A Red Flag Warning, which indicates hazardous fire weather conditions are imminent or occurring, was not issued because the relative humidity did not fall below the NWS’s 15% threshold (established for warm-season wildfires). But the high-wind warning did trigger a county-wide burn ban in Boulder County, the location of the Marshall Fire.

There were several unusual aspects of this windstorm, including the astonishing duration of sustained hurricane-force winds out of the southwest, Benjamin said, which blew without a break for 11 hours. “For the wind to keep going for that many hours, out of all the unique aspects of this storm, that was one maybe most important for that fire to spread the way it did,” he said.

Two small fires become an inferno

At about 11 a.m., two accidental ignitions sparked grass fires just east of the intersection of Highway 93 and Marshall Road, three miles from Superior. Fanned by relentless winds throwing embers on gusts of up to 100 mph, the fire raced across open space and pasture desiccated by six months of drought, arriving at the edge of the two towns as a roaring wall of flame in less than an hour.

Thanks in part to frantic social media posts spreading the alarm, 50,000 residents successfully evacuated in bumper-to-bumper traffic surrounded by thick smoke and flying embers as the firestorm devoured subdivisions, restaurants, shopping centers, and a brand-new Marriott Hotel. Officials said it was nothing short of miraculous that only two people perished.

Long after night fell, the winds finally subsided and firefighters began to stop the spread of the flames. The first significant snowfall of the season arrived the following day, gently covering the smoldering ruins.

“During most of the severe windstorms of 1960s, 70s and 80s in and around Boulder, the wind observations detected significant lulls in the wind,” said Paul Schlatter, the science and operations officer for the local National Weather Service forecast office and a Boulder native. “You’d have 120 mph gusts, then almost calm for ten minutes or more, then whoosh – it would come back gusting over 100 mph.”

“The measurements we’ve seen show that during the Marshall Fire, the wind didn’t fluctuate much over the course of the event,” said Schlatter. “It was always out of the southwest, gusting at 60 to 100 mph for 10 to 11 hours.”

New tools to protect lives and property

While the combination of a very accurate model forecast and experienced meteorologists produced an early and accurate warning, the authors said living through the Marshall Fire has helped underscore ways to improve readiness, forecasts, and warning dissemination.

Advances in numerical weather models will provide longer lead times and more geographical accuracy, the authors said. New tools, like the Global Systems Laboratory’s Hourly Wildfire Potential Index, which distills modeled predictions of temperature, winds, and soil moisture from national models into a geographical fire risk index across the nation during the day, can improve awareness of rapid changes in hazardous fire weather conditions for first responders.

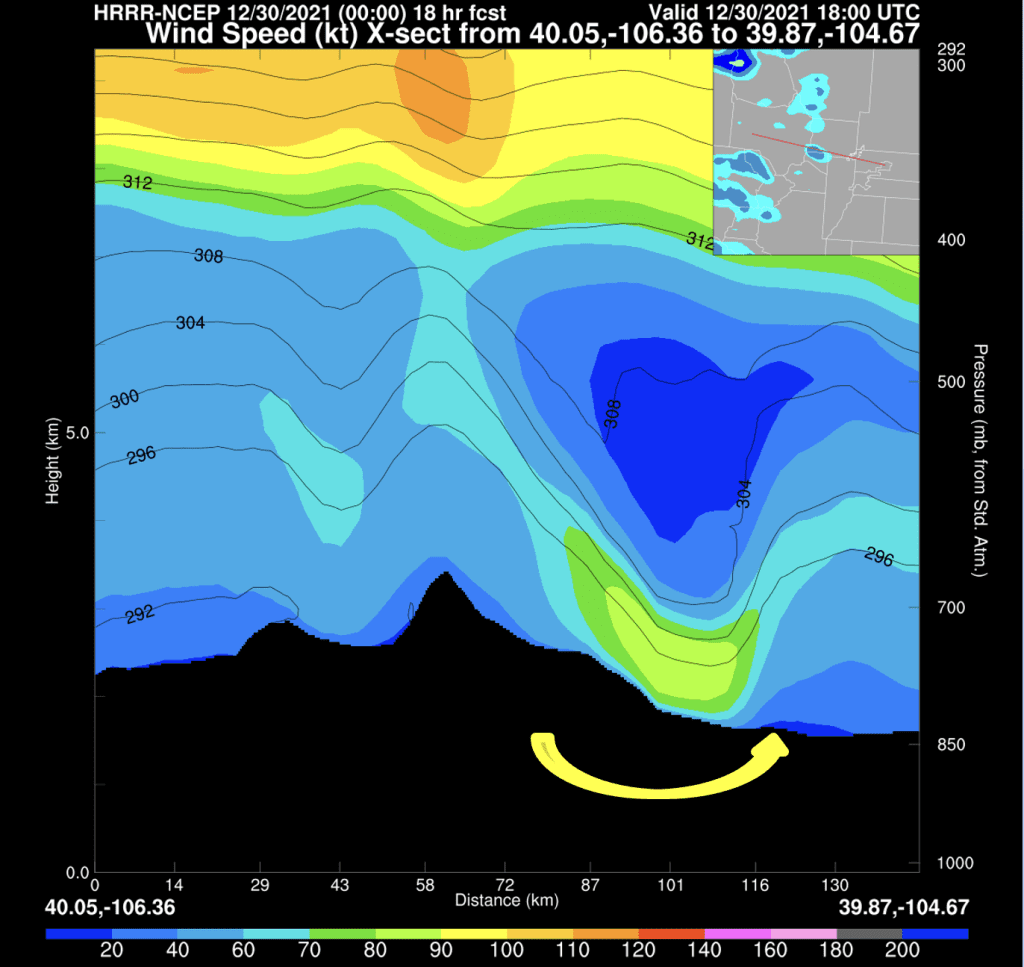

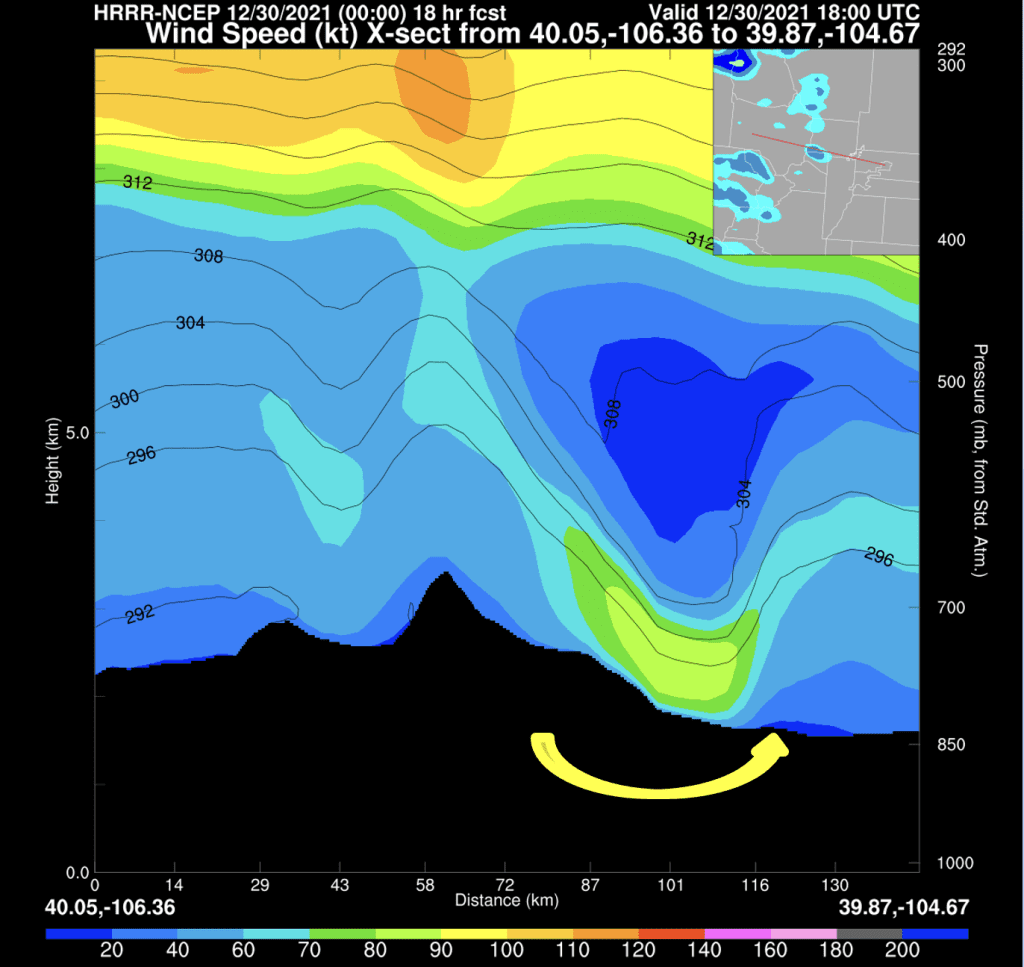

These are two views of wind patterns over the Marshall Fire at midday on December 30, 2021 as seen from south of Boulder, facing north. The graphic on the left depicts the HRRR forecast, generated at 5 p.m. on Wednesday December 29 for 11 a.m on Thursday December 30. It shows wind speed (in knots) from the surface up to the jet stream over the Continental Divide. In the photo at right, the yellow arrow captures the airflow associated with turbulence generated by the windstorm as it raced over the fire during the early afternoon.

Researchers recommended the strict relative humidity criteria for Red Flag Warnings could be relaxed, and additional focus devoted to the potential rate of fire spread – especially in the face of extreme winds. Fire warnings, explored by National Weather Service forecast offices in the Southern Great Plains over the past few years, could improve communication of the severity of the risk once a wildfire is burning. These could be disseminated via the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s existing Wireless Emergency Alerts, which can be broadcast from cell towers to any compatible mobile device in a locally targeted area.

A climate connection?

While the Marshall Fire’s peak winds were extreme, the strongest windstorms occurred more frequently 30-50 years ago, said several of the co-authors, veteran meteorologists.

In the 10 years between 1996 and 2006, Schlatter said, Boulder and the surrounding wind-prone areas at the base of the Rocky Mountains experienced wind gusts of at least 80 miles per hour on an average of 8.5 days per season and gusts of at least 103 mph on 2.1 days per season. On average, wind gusts of at least 115 mph occurred on at least one day per year.

But between 2013 and 2022, gusts of at least 80 miles per hour have happened on average only 5.5 days per year, and gusts of 103 mph or more on less than 1 day per year. Gusts of 115 mph or more are now happening only once every five years.

“This is a limited record, but the trend over the last 30 or so years is real,” said Schlatter. “These mountain wave events, including the most intense, still occur but are becoming less frequent.”

Nevertheless, mountain wave events will continue to occur, accompanied by the risk of catastrophic wind-driven fires. “Ongoing research like this can help us expand lead times for fire weather warnings as we better understand the details of extreme wind events and provide more real-time information when every minute counts,” Benjamin said.

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications: theo.stein@noaa.gov .

NOAA’s Global Systems Lab will host a webinar on new research analyzing the Marshall Fire on Tuesday January 9, 2024. Learn more by visiting their website.