NOAA, Schmidt Ocean Institute, and partners recently embarked on the In Search of Hydrothermal Lost Cities expedition on the Schmidt’s Research Vessel Falkor (too) to locate and observe hydrothermal vent activity along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The team successfully located never-before-seen black smoker vents near the Puy de Folles vent field and the impressive ecosystems they support. Discovering new vent systems is important to science since their chemical makeup is suspected to be closest to the conditions that facilitated life’s origin on our planet.

In Search of Hydrothermal Vent Lost Cities Expedition

A team of researchers recently embarked on an expedition to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in search of active hydrothermal vents. During this expedition, the team searched for vents similar to the largest known hydrothermal vent structures in the ocean, the Lost City vents, that tower 65 to 200 feet above the seafloor. Researchers used the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) SuBastian to reach the depths at which these vents are located. The ROV was equipped with a suite of scientific equipment to support data and sample collection, such as cameras; conductivity, temperature, and depth sensors (CTDs); pressure depth sensors as well as a newly developed NOAA SBIR funded methane analyzer, and more.

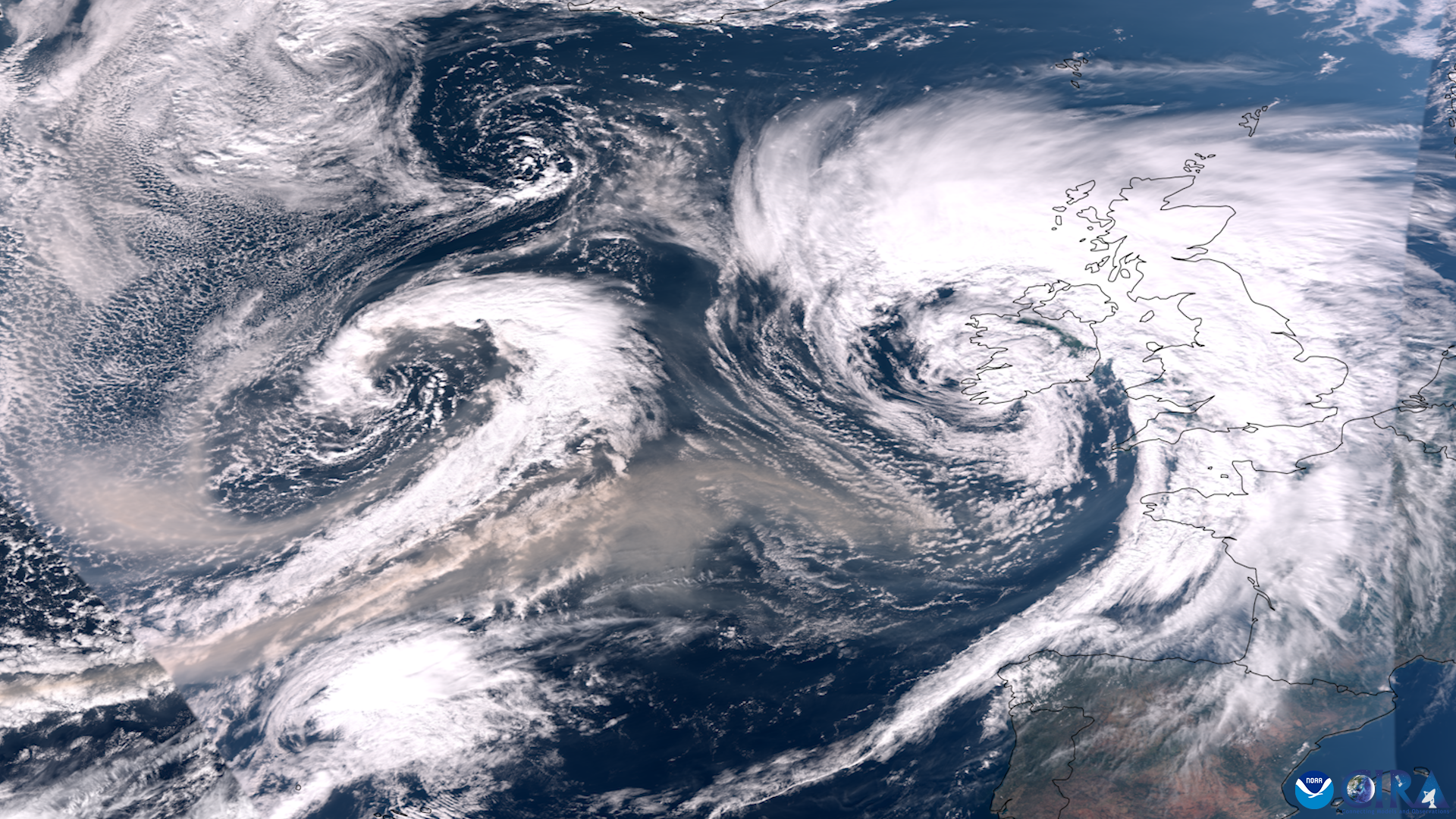

Once researchers were underway on the expedition, bad weather prevented them from exploring the Kane Fracture Zone, which was their primary location for exploration. While they waited for the weather to improve, the team decided to test their strategy for finding active hydrothermal vents at the Puy des Folles volcano. Previous expeditions have explored the volcano with human-occupied vehicles, towed cameras, and dredges, finding no active venting, but noting that hydrothermal plumes were present. By combining different research tools, the team of researchers successfully discovered spectacular black smoker vents covered in shrimp, with 645° Fahrenheit water billowing out.

“There were audible gasps, hoots and high-fives throughout the control room, after months of planning and preparation, we were grateful to start this expedition on a high (temperature) note”

What is a hydrothermal vent?

Hydrothermal vents form when seawater seeps through fissures in the ocean crust in the vicinity of spreading centers or subduction zones (places on Earth where two tectonic plates move away or towards one another). The cold seawater is heated by hot magma and reemerges to form the vents as superheated, chemical-rich water, sometimes reaching temperatures over 700° Fahrenheit.

Scientists first discovered hydrothermal vents in 1977 while exploring an oceanic spreading ridge near the Galapagos Islands. These explorers were amazed to not only find life thriving in these hostile environments, but also to find species never seen before in any other place on the planet. Most hydrothermal vents occur in the deep sea, where there is no sunlight, so life that lives on and around hydrothermal vents depends upon chemosynthesis, a chemical process that results from the interaction of seawater and hot magma associated with underwater volcanoes.

Since their initial discovery, multiple types of hydrothermal vents have been observed. The two main types of vents are “white smokers” which are chimneys formed from deposits of barium, calcium, and silicon, which are white; and “black smokers” which are chimneys formed from deposits of iron sulfide, which is black. The vents that were recently discovered on the Lost Cities expedition are examples of black smokers.

The hydrothermal vents in this region are driven by a chemical process known as serpentinization. Serpentinization is a heat-producing chemical reaction between seawater and mantle rocks that provides a source of chemical energy for life in the deep ocean. This type of venting is not well documented or understood. Samples collected during this cruise will give scientists additional clues to these systems.

Why is it important to study hydrothermal vents?

Hydrothermal vents affect the chemistry and circulation in the oceans, providing natural laboratories for studying volcanic eruptions, methane release, the effects of ocean acidification on marine biological communities, and more. They also support unique deep sea ecosystems including chemosynthetic animals and extremophile microbes that live at or beneath the seafloor and are released into the ocean in hydrothermal plumes. The properties of these hydrothermal microbes are useful for the development of potential drug therapies. These vent ecosystems are delicate communities, and with interest in deep sea mining rising internationally, it is important to identify active vent fields and the ocean services they provide to determine if protection is needed.

Scientists have determined that life on Earth began approximately 3.8 billion years ago and hypothesize that this first occurred in the ocean’s hydrothermal vents. Studying life at hydrothermal vents provides clues to help scientists learn more about the origins of life on Earth—and potentially on other planets!