New research shows they cause more crashes than previously recorded

A new research paper from NOAA’s Air Resources Laboratory published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society finds that dust storms – previously assumed to be rather rare and isolated to particular regions – are contributing to a larger number of U.S. traffic fatalities than are recorded. This research also proposes modifications to the current reporting classifications to more accurately capture dust storm impact.

“We found that dust events caused life losses comparable to events like hurricanes and wildfires in some years,” says Daniel Tong, author of the paper and research scientist at NOAA and an associate professor of Atmospheric Oceanic and Earth Sciences at George Mason University. “Greater awareness could reduce crashes and possibly save lives.”

Tong’s team examined records from 2007-2017 and estimated there were 232 deaths from dust storm related traffic events, while previous datasets reported a total of 10 deaths, or a yearly average of one dust storm-related death for the same time period.

Dust storms can panic unprepared drivers, blocking all visibility behind and in front of a car, and cause people to become disoriented or slam into unseen obstacles. Dust on the pavement can also cause vehicles to lose traction and spin out of control.

Dust related fatalities in the U.S. are most frequent in the Southwest where winds from strong thunderstorms kick up dust and sand in desert landscapes. But a dust storm can occur anywhere there’s loose soil and wind. Smaller, more localized windblown dust events often happen when winds cross fallow farmlands, construction sites or dry landscapes in any part of the country.

Dust storms missing in reporting

Tong had long been concerned that fatalities from dust storms were being undercounted.

“We would see that huge highway crashes had occurred during dust storms, but later when we looked, we didn’t always see those events reflected in the official, national records,” he says.

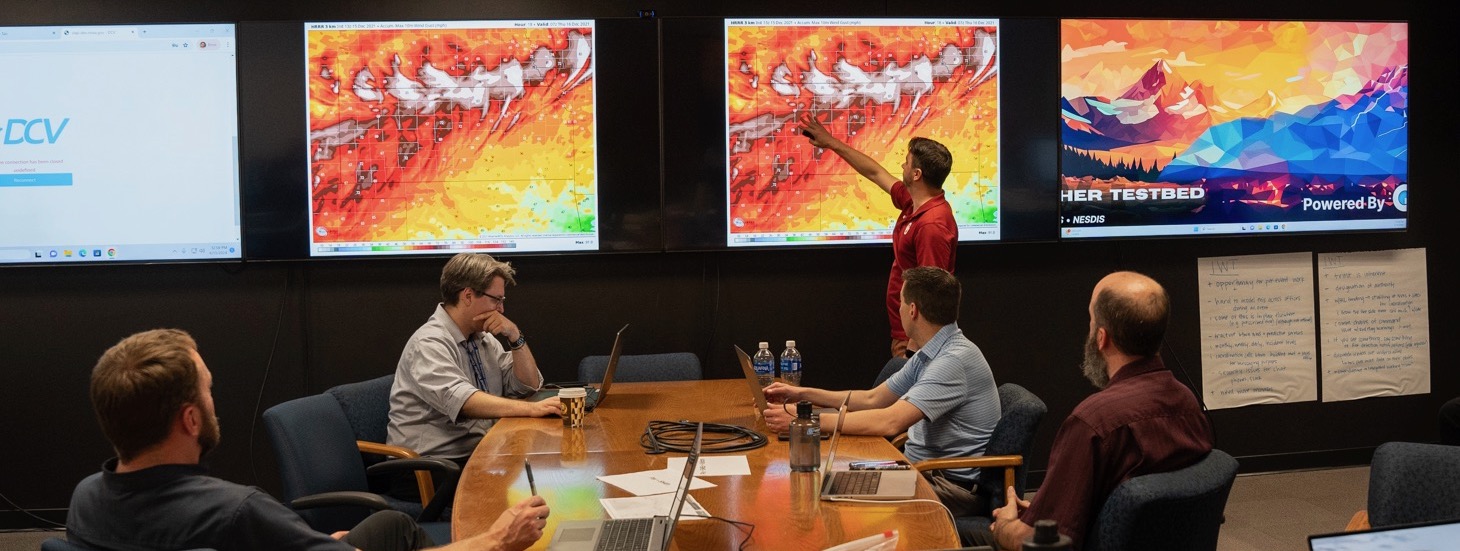

His team examined two of NOAA’s own databases, the Storm Events Database (Storm Data) and the Natural Hazards Statistics (NHS – also known as HazStats), as well as the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS).

He found that labels in these databases varied widely for dust storms. He also found that some states that feed information into the FARS system do not count dust storms at all.

Tong’s team pulled out data regarding fatal crashes from these databases using the keywords “dust” and “sand” as explicitly described in the event narratives. They also created new datasets using mass media reports and social media accounts of dust storms, including those that were part of thunderstorms or other fronts.

By cross-checking this way, they found that the number of deaths from dust storms ranged from 14-32 per year – many more than the 10 that had previously been officially recorded over the same ten year period.

A clearer road ahead

Tong recommends several ways that dust storm accounting could be improved:

- States could use a consistent reporting form for the cause of crashes.

- HazStats could allow multiple classifications for a single weather event.

- Weather agencies and law enforcement could collaborate in both the identification and the reporting of dust storms in order to achieve greater accuracy.

“Dust events pose a more constant risk and are a greater source of weather-related deaths in most years than other, much larger storm systems,” Tong concludes. “Dust storms are sometimes small and local, but we need people to know they can be deadly.”

Media contact:

Alison Gillespie, Alison.Gillespie@noaa.gov, (202) 713-6644