From predicting smoke movement from massive wildfires, to investigating how marine life is responding to a quieter ocean, 2020 was a big year for NOAA science. As this unprecedented year draws to a close, we’re looking back at some of our biggest research endeavors in 2020. Here are 5 of our most-read stories from the last year.

NOAA models track smoke movement – and locust swarms

The western U.S. endured an explosive wildfire season in 2020. Record fires scorched Colorado, which saw its three largest wildfires in state history in October, and tore through California, with over 4 million acres burned in the state since the beginning of the year, according to Cal Fire. As the planet warms, California’s risk of fall season wildfires has gone up, with fires stretching into December.

All that fire means a lot of smoke – over the summer, residents on the East Coast of the U.S. experienced hazy skies as smoke from the West traveled across the country. For the last three years, despite being an experimental model, NOAA’s High Resolution Rapid Refresh-Smoke (HRRR-Smoke) has been depended on by forecasters, who use it to determine how far smoke will travel and how thick it will be. HRRR-Smoke played a pivotal role in forecasting smoke movement this summer, and scientists are now using it to build the next generation of air quality models. HRRR-smoke was transferred to National Weather Service operations on December 2.

This year also saw NOAA scientists team up with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization to create a new model to predict locust swarms across Africa and Asia. The new model is based on NOAA’s workhorse HYSPLIT dispersion model that tracks pollution from wildfires, volcanoes and industrial accidents. It’s now helping farmers on two continents prepare for and mitigate some of the worst locust swarms in a quarter century.

Scientists explore the impact of the COVID-19 response on the environment

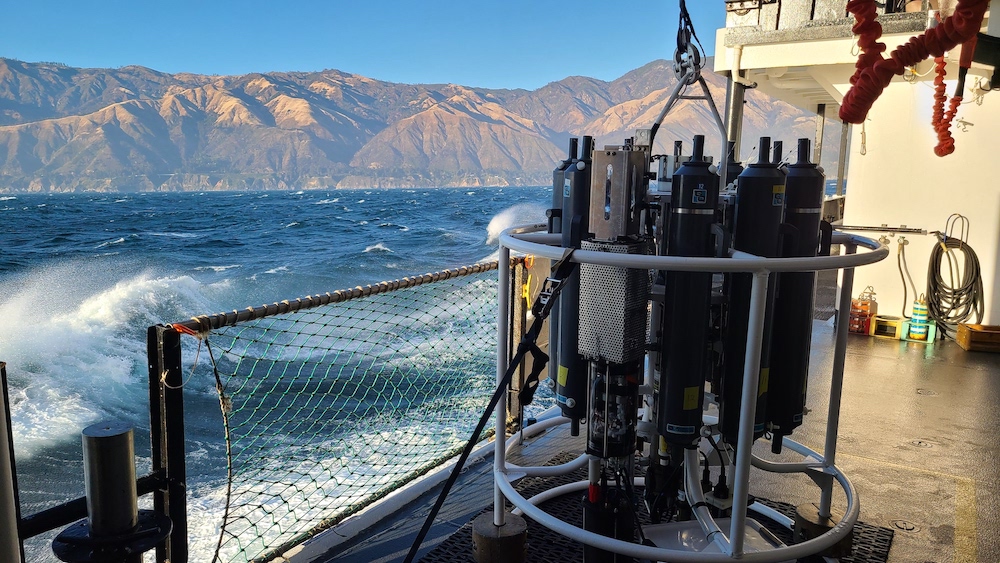

You probably noticed it: At the beginning of the pandemic, when COVID-19 drove many people indoors, there were fewer cars on the road, fewer planes in the sky…and less air pollution. This year, NOAA launched a major effort to study the environmental impact of reduced vehicle traffic, air travel, shipping, manufacturing and other activities on Earth’s atmosphere and oceans.

NOAA scientists are investigating the impact of decreased pollution in specific areas, and will analyze measurements collected from its global sampling network of contract airplanes, towers and ground sites at laboratories in Boulder, Colorado and College Park, Maryland. In the oceans, NOAA scientists are assessing impacts of reduced underwater noise levels on marine life (check out what they’ve found so far). Stay tuned for the first scientific studies that come out of this groundbreaking effort.

Carbon dioxide continues to rise

Concentrations of carbon dioxide, the main driver of human-caused climate change, continue to rise in our atmosphere, as evidenced by measurements at the Mauna Loa Observatory. Atmospheric CO2 measured at Mauna Loa reached a seasonal peak of 417.1 parts per million for 2020 in May – the highest monthly reading ever recorded.

“Progress in emissions reductions is not visible in the CO2 record,” said Pieter Tans, senior scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory. ”We continue to commit our planet – for centuries or longer – to more global heating, sea level rise, and extreme weather events every year.”

CO2 emissions temporarily fell in the first half of 2020, as the pandemic forced many around the world to stay indoors. However, this reduction was not large or long-lived enough to curb the overall rate of increase of CO2 emissions this year.

“The buildup of CO2 is a bit like trash in a landfill,” said geochemist Ralph Keeling, who runs the Scripps Oceanography program at Mauna Loa. “As we keep emitting, it keeps piling up. The crisis has slowed emissions, but not enough to show up perceptibly at Mauna Loa. What will matter much more is the trajectory we take coming out of this situation.”

Dungeness crab larvae are already showing effects of ocean acidification

Ocean acidification acidification along the US Pacific Northwest coast is impacting the shells and sensory organs of some young Dungeness crab, a prized crustacean that supports the most valuable fishery on the West Coast, according to a 2020 NOAA-funded study. Prior to this study, it was thought that Dungeness crab were not vulnerable to current levels of ocean acidification, which occurs as the ocean and Great Lakes absorb atmospheric CO2, altering the water’s pH.

“If the crabs are affected already, we really need to make sure we start to pay much more attention to various components of the food chain before it is too late,” said lead author Nina Bednarsek, senior scientist with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project.

A new roadmap for tackling ocean and Great Lakes acidification

As evidenced by the dungeness crab, acidification is already impacting marine life. To tackle that challenge, NOAA unveiled its new 10-year research roadmap to help the nation’s scientists, resource managers, and coastal communities address acidification of the open ocean, coasts, and Great Lakes.

“Ocean acidification puts the United States’ $1 billion shellfish industry and hundreds of thousands of jobs at risk,” said Kenric Osgood, Ph.D., chief of the Marine Ecosystems Division, Office of Science and Technology at NOAA Fisheries Service. “Understanding how ocean acidification will affect marine life and the jobs and communities that depend on it is critical to a healthy ocean and blue economy.

Our science won’t be slowing down in 2021! Stay up to date with the latest NOAA Research news by following us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

*Note: We previously stated that the number of acres burned in California exceeded 1.4 million this year. In fact, it exceeds 4 million. This story has been updated to reflect this change.