Dr. Leticia Barbero is a chemical oceanographer at NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami. In her role, she works with NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory to study the carbon dioxide system in the ocean, specifically ocean acidification in the coastal waters of the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico.

What drew you to your current career or field?

I think I was 16 years old when I told my parents I wanted to study marine sciences in Norway. I have no idea why I wanted to go to Norway specifically. I quickly discarded the idea of Norway, but not oceanography. I come from an inland city about three to four hours from the nearest beach, but I guess I always liked the sea and all the secrets it seemed to hold. I also liked the idea of a multidisciplinary degree where I had the chance to study chemistry, biology, physics and geology. As I completed my undergrad, climate change and how it affects the oceans was appealing to me, and that’s how I ended up doing my Ph.D. studying the CO2 system.

What projects or research are you working on now?

My work is mostly focused on ocean acidification studies. Ocean acidification (OA) is the decrease in pH that occurs as a result of increased carbon concentrations in the ocean. The increased acidity (lower pH) can have significant impacts on ecosystems and organisms. My group collects carbon chemistry data in the East and Gulf of Mexico coasts of the U.S. through a variety of approaches including ships of opportunity, discrete samples or specific research cruises. I lead our group’s OA cruises in the Gulf of Mexico. These cruises take place every four years and they incorporate a multidisciplinary team of scientists collecting data on the physics, chemistry and biology of our coastal waters, all with the purpose of monitoring trends of OA and how it could impact local communities.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

I like that it is not monotonous. Sometimes I am sitting in my office all day, but other times I work in the lab with samples, or I am travelling to meet with colleagues to present our results. And then every other year I get to go on research cruises, where I feel really seasick at first (and think I’ll never do this again) but after that really enjoy the opportunity to work with a diverse group of people. And did I mention the amazing sunrises/sunsets and starry skies?

Also, lately I have had the opportunity to engage in outreach activities providing guidance and training to groups that are interested in starting their own OA programs. It is amazing to meet these people who are so passionate about the environment and about establishing good OA monitoring programs, even with very limited resources. They are truly humbling and a real inspiration to me.

What was the best advice ever given to you that helped you become successful?

Right before I was chief scientist for the first time on a research cruise and in charge of about 30 scientists and a 45-day expedition, someone told me: “You are going to have to make a lot of decisions on this cruise, some big, some small. The key thing is to decide. It is better to decide and potentially make a mistake than to not be able to make up your mind.” I think that is excellent advice when you are faced with a problem. On a cruise, people are relying on you to provide guidance. You may not know the right option with certainty, there may not even be a “best option,” but just make your best educated decision and move on to the next item at hand.

Looking back, what would you tell yourself when you were 12 years old? Or what advice would you give to a woman just starting out in her career?

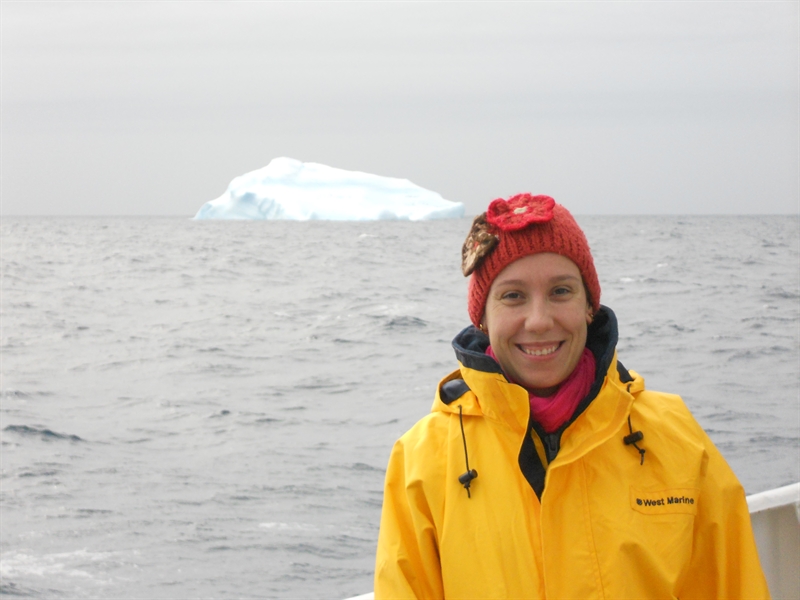

I’d tell myself I’m afraid you will not become an astronaut, but you will sail among icebergs and whales, and you will witness the most amazing starry nights you could ever imagine from the middle of the ocean. You will get to travel the world thanks to your job. Also, you will never really miss not having to study astrophysics.

To a woman starting her career I’d tell her believe that you are better than you give yourself credit for, because you are, and lose your fear of asking for more. Also, if you are thinking of going for of Ph.D. or starting a position in a new lab, try to talk to the people who work for your potential new advisor/boss (students, techs, administrative assistants) to get an idea of what kind of boss you are going to have. They might have an impressive publication record but be awful advisors.