Dr. Meghan Cronin works at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, where she leads the Ocean Climate Stations group. The group maintains two heavily instrumented surface moorings in the North Pacific — the Kuroshio Extension Observatory (KEO) and a NOAA surface mooring at Station Papa — which use sensors to monitor the air-sea exchanges of heat, moisture, momentum and carbon dioxide, as well as upper ocean conditions.

Meghan is also lead Principle Investigator for a project testing saildrone — a new unmanned surface vehicle that that can carry a similar suite of sensors as a moored buoy — in the tropical Pacific. She and her team are showing how you can launch these saildrone from shore, have them sail thousands of miles to the study site, and then return home after the experiment is complete.

What drew you to your current career or field?

In college I started as a music major, but much to everyone’s surprise (including myself) I then switched to physics. A summer job doing oceanographic research at the University of Rhode Island in Professor Randy Watts’ lab cinched the deal. I got my PhD from URI 9 years later and Randy Watts was my Ph.D. advisor. Whether it is an internship, a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU), or a work-study experience, these are great opportunities to find your path and mentors. Likewise, I encourage NOAA scientists to engage with the NOAA Office of Education programs, as well as with cooperative institute internship programs. An Ernest F. Hollings Undergraduate Scholar I mentored is lead author on a paper, currently under review in Journal of Climate, that was a direct result of her summer work with me.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

There are so many things I love about this career and job. Doing important work, where you come up with an idea and see it through, is very satisfying. I work with colleagues at universities and laboratories across the country and around the world. Right now I’m lead author on a strategy paper for making breakthrough improvements for quantifying the amount of heat exchanged between the oceans and atmosphere. Oceanic heating of the atmosphere is critically important for hurricane development, El Niño, decadal oscillations, and other ocean-atmosphere coupled phenomena. Better quantification of these heat exchanges could lead to improvements in their predictions. I have 26 coauthors from US, Japan, France, UK, Sweden, South Africa and Russia. When we have telecons, there’s always someone who has to call in late at night or early, early in the morning. It’s fun! When I come to work in the morning, I look forward to my day ahead. At the end of the day, I generally feel like I accomplished something.

What’s been your favorite (or proudest) moment in your career so far?

I have had many proud and happy moments. But one stands out — It was June 2005 and I was on the R/V Revelle. The second deployment KEO mooring’s buoy was hanging from the crane before going over the side of the deck. It seemed like everyone on the ship had a hard hat and a tag line. Everyone on the ship was focused on making this a success. I knew too that folks from DC to Seattle to Japan and beyond had placed confidence in me and this team and were hoping for success. We are now on the 15th deployment year. That’s success!

What challenges have you faced as a woman in your career/field, or in general, and how have you overcome them?

That was a 3-week cruise in 2005. I also spent a week in Japan preparing for this cruise and talking with JAMSTEC scientists about forming a NOAA-JAMSTEC partnership that has been central to the success of KEO. At the time our daughter was in first grade and my husband was working and had a long commute. So for that month, my husband would have to drop her off at the before/afterschool care at 7 AM and then pick her up at 6 PM.

It was challenging. No — it was horrible. When I got back, we reconsidered things. Brian decided to quit his job and take on the “homemaker” role (volunteering at the school, soccer carpool, etc.). This also allowed him to pursue his musical interests.

Looking back, what would you tell yourself when you were 12 years old? Or what advice would you give to a woman just starting out in her career?

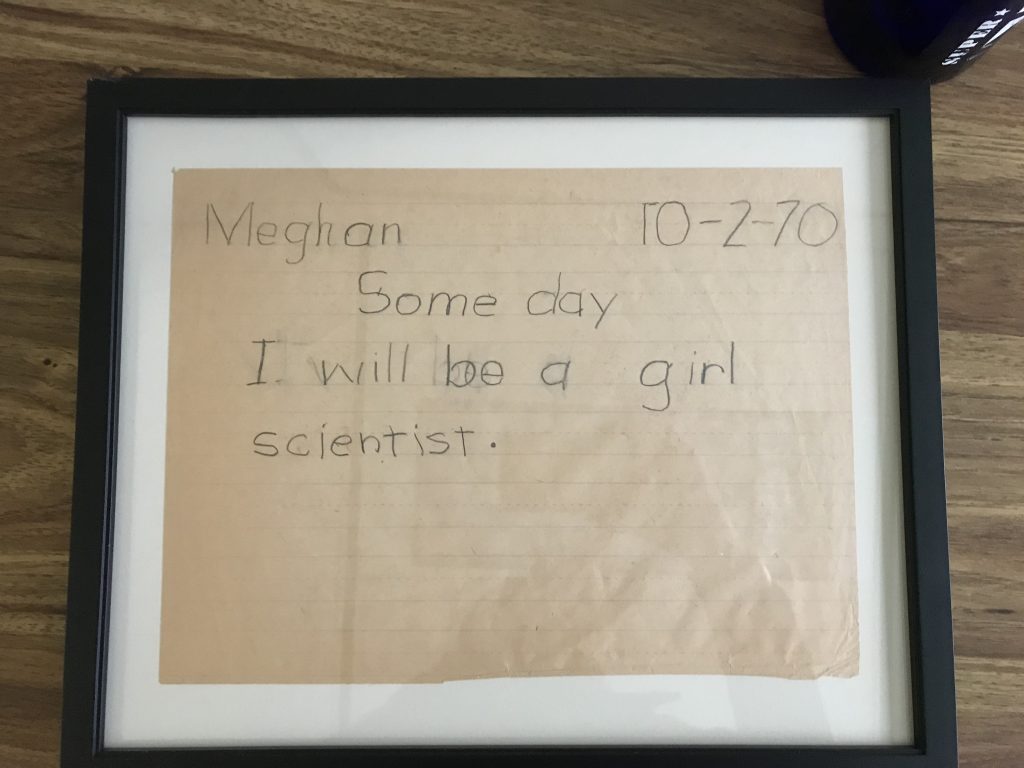

A few years ago, while cleaning out my mother’s garage, I came across an yellowed school paper with carefully-written lettering saying:

I now have this framed in my office. I would have been 7 years old (2nd grade). I don’t have any memory of this, but can piece it together. In first grade I had a teacher who shared the excitement of science. I remember studying maggots on a dead animal in the walkway behind our classroom and doing experiments on fluoride, which was just being put into the city water. My second grade teacher was much more traditional. I enjoyed a science class in high school, but my switch to physics in college seemed like it came out of nowhere.

If I could talk to that 7-year-old girl, I would say, “Good choice! Science is Fun! And thanks for reminding me that I’m a girl scientist. I normally just think of myself as a

scientist. But in fact, we bring our whole selves to what we do. My being a girl and who I am affects everything I do — the problems that I pick, how I form a team, how I work

through a problem, how I explain it. When girls are not included, some problems don’t get solved. Science needs good ideas from girls and girls to follow-through on these

ideas. Go for it!”