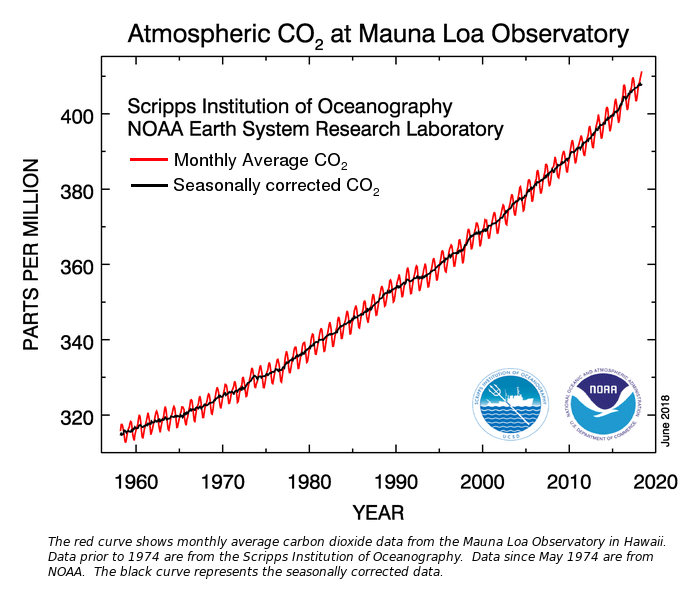

Peak carbon dioxide levels surpass 410 parts per million for April and May

Carbon dioxide levels measured at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory averaged more than 410 parts per million in April and May, the highest monthly averages ever recorded, scientists from NOAA and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego announced today.

Primarily driven by fossil fuel combustion, increasing carbon dioxide levels are tracked closely by the world’s scientists as a measure of how human activity is changing the planet’s atmosphere. This year, the monthly average for carbon dioxide (or CO2) exceeded 410 ppm for the first time in April. The average for May peaked at 411.25 ppm.

“CO2 levels have been growing at all-time record rates because consumption of coal, oil, and natural gas are also at historically high levels,” said Pieter Tans, lead scientist of NOAA”s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network. “Today’s emissions will still be trapping heat in the atmosphere thousands of years from now.”

The Mauna Loa observatory is ideally located for monitoring CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Situated at more than 11,000 feet above sea level in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, the site gives researchers the opportunity to sample air that has been well-mixed during its passage across the Pacific and, thanks to its altitude, is minimally influenced by local vegetation or local pollution sources.

Measurements are independently validated

Independent measurements of CO2 at Mauna Loa are made by scientists with NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. Initiated by Scripps scientist Charles David Keeling at the NOAA weather station on Mauna Loa in 1958, continuous, on-site observations have been made for the past 60 years, with NOAA’s measurements beginning in 1974. NOAA air samples are also shipped to NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado for verification, as well as further analysis.

Keeling was the first to recognize that CO2levels have a distinct seasonal cycle driven by the Northern Hemisphere’s growing season. During the northern summer, plant growth removes enough CO2 from the atmosphere during photosynthesis to temporarily overcome the amount added by decaying vegetation and by fossil fuel consumption. During the northern fall, winter and most of spring, CO2 levels rise as decaying vegetation and fossil fuels are turned back into CO2 gas, which is released back into the atmosphere. Keeling’s son, scientist Ralph Keeling, now runs the Scripps program at Mauna Loa.

“Many of us had hoped to see the rise of CO2 slowing by now, but sadly that isn’t the case,” said Keeling. “It could still happen in the next decade or so if renewables replace enough fossil fuels.”

Analysis shows the growth rate of CO2 in the atmosphere is accelerating, Tans said. It averaged about 1.6 ppm per year in the 1980s and 1.5 ppm per year in the 1990s, but increased to 2.2 ppm per year during the last decade.

From 2016 to 2017, the global CO2 average increased by 2.3 ppm – the sixth consecutive year-over-year increase greater than 2 ppm. Prior to 2012, back-to-back increases of 2 ppm or greater had occurred only twice.

“If the current rate of increase holds steady for another two decades, global CO2 will likely be well past 450 ppm in 2038,” Tans said.

Learn more at: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/data.html

For more information, contact Theo Stein at NOAA Communications: theo.stein@noaa.gov or 303-497-6288