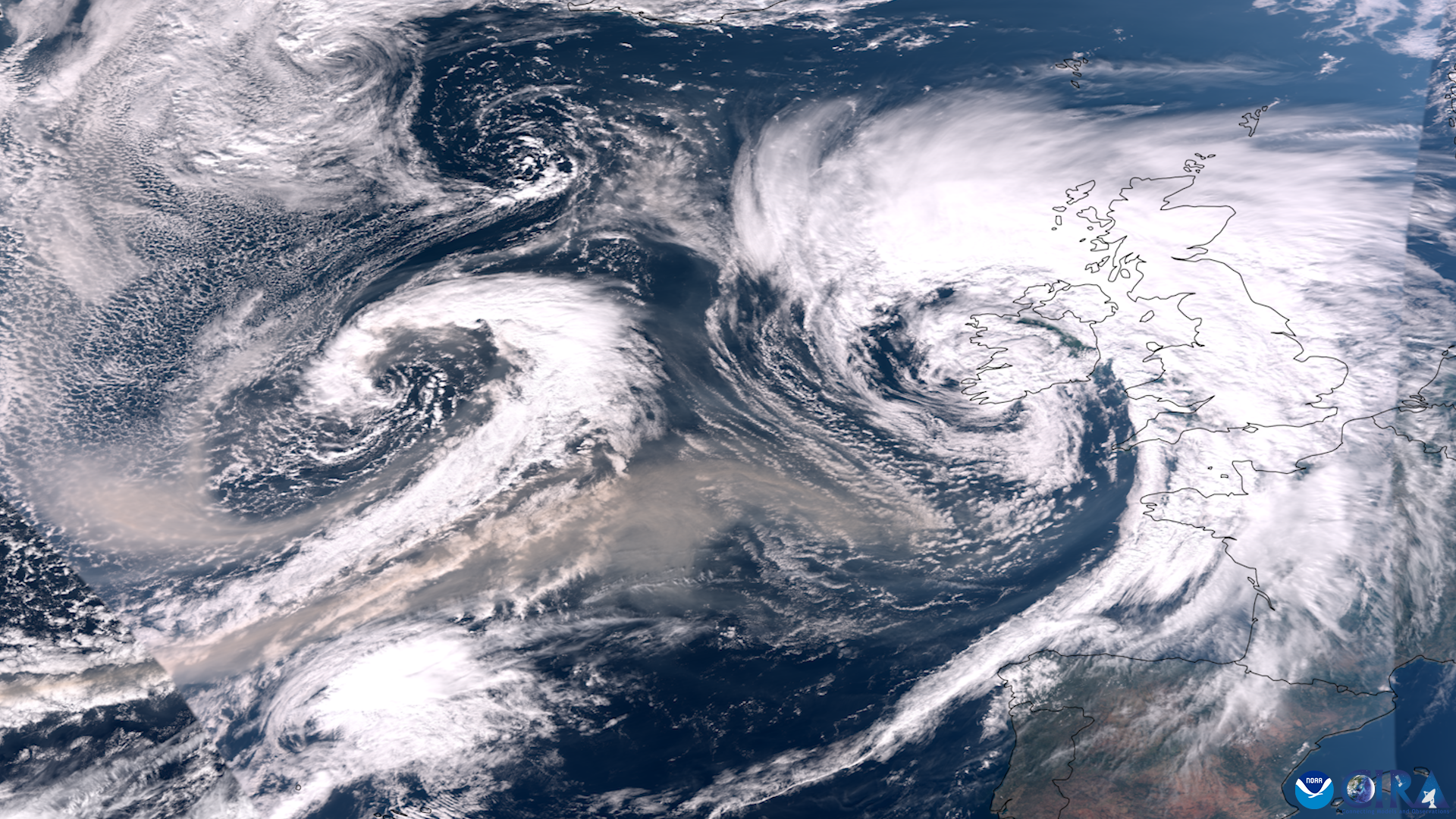

The Earth’s upper stratosphere is cold and remote. Few planes are capable of flying that high or lingering for long. So while the stratosphere is important for understanding climate change – and is routinely probed from a few locations by small balloons for monitoring the planet’s protective ozone layer, the number of direct measurements taken at these altitudes are comparatively few and far between.

That’s about to change.

This fall, scientists from NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, are fine-tuning a low-tech, cost-effective system for lifting a small payload of specialized measuring instruments to the edge of space, and then guiding it back to the launch location. Nicknamed HORUS, after the falcon-headed Egyptian god, the High-altitude Operational Return Unmanned System relies on a standard weather balloon to hoist a small, remote-controlled glider carrying scientific instruments tail-first to altitudes of up to 90,000 feet. When the balloon pops, the glider, with its six-foot wingspan, can be piloted to a soft landing at the initial launch site.

The system has the potential to usher in a new era of atmospheric research, said Colm Sweeney, who leads the lab’s aircraft program.

“We still have some hurdles to overcome. but conceptually we’ve licked a big problem … finding a good way to recover a balloon-borne vehicle,” Sweeney said. “Now we can launch from lots of places we couldn’t launch before – rough terrain, islands, even ships at sea.”

During a May test flight at the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California, HORUS successfully returned from a release point 75,000 feet above the desert floor, trailing a parachute to a smooth belly landing just yards from its initial launch site.

NOAA scientists are now working to obtain a Federal Aviation Administration Certificate of Authorization for routine HORUS flights in the Pawnee Grasslands of northeast Colorado. With a successful flight in Colorado, the technology will become officially operational.

How is the upper atmosphere sampled?

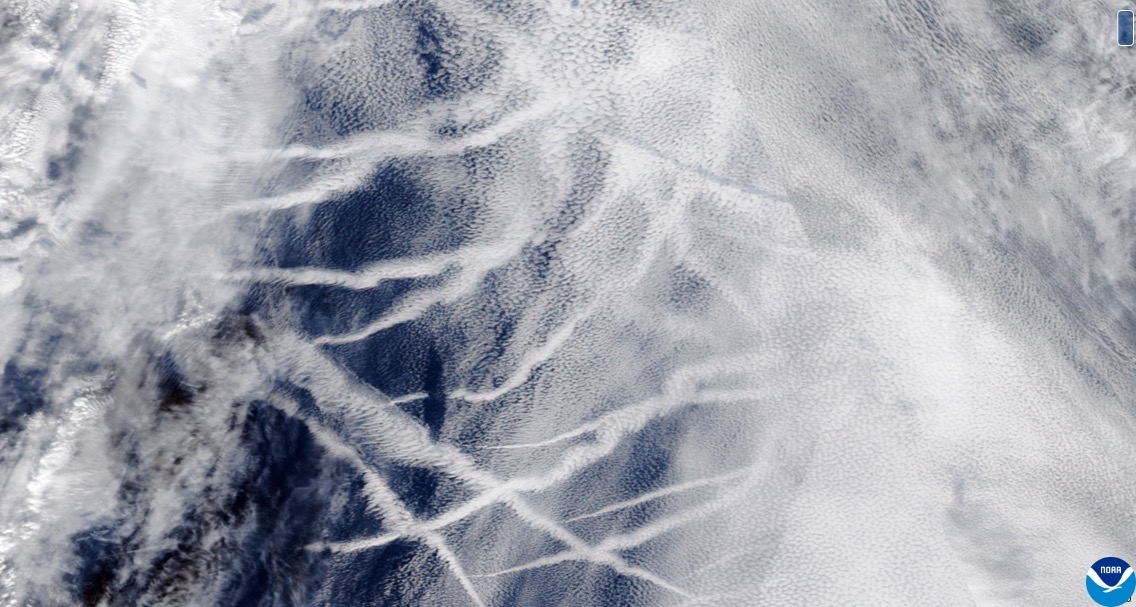

Weather balloons have long been the most common method for sampling the upper atmosphere, but recovering the instrument payload can be challenging. After the balloon pops, the instruments – typically encased in a styrofoam box – descend back to the surface supported by a parachute. But winds aloft can cause instruments to drift many miles during the ascent and descent, and land randomly in hard-to-reach locations. As a result, most research balloon launches are planned over rural areas that are less populated and easy to access.

In contrast, the HORUS glider can be launched from virtually anywhere and reliably return to the launch point. During the May test flight, HORUS reached speeds of more than 200 knots over the ground at the beginning of the glide phase, more than sufficient to navigate the 60-knot winds that it encountered at 40,000 feet.

In addition, the HORUS airframe provides a flexible space for up to 10 pounds of scientific instrumentation, which will allow scientists to capture air samples and make in-situ measurements.

Why is this technology revolutionary?

Today’s weather and climate models need vast amounts of accurate, high-resolution observations covering large areas of the atmosphere over long periods to generate accurate forecasts and predictions. With the ability to efficiently recover high-value, high-accuracy instrumentation, HORUS offers a cost-effective way to expand high-altitude air sampling globally and improve the accuracy of data used by climate and weather models.

Scientists also use research aircraft, which can carry heavier payloads, but aircraft rarely reach 75,000 feet and are too expensive for frequent sampling required by next-generation climate models. Satellites, which are even more costly, provide continuous overwatch of the atmosphere, but their instruments make estimates of atmospheric composition based on the reflection or absorption of light, rather than direct measurements.

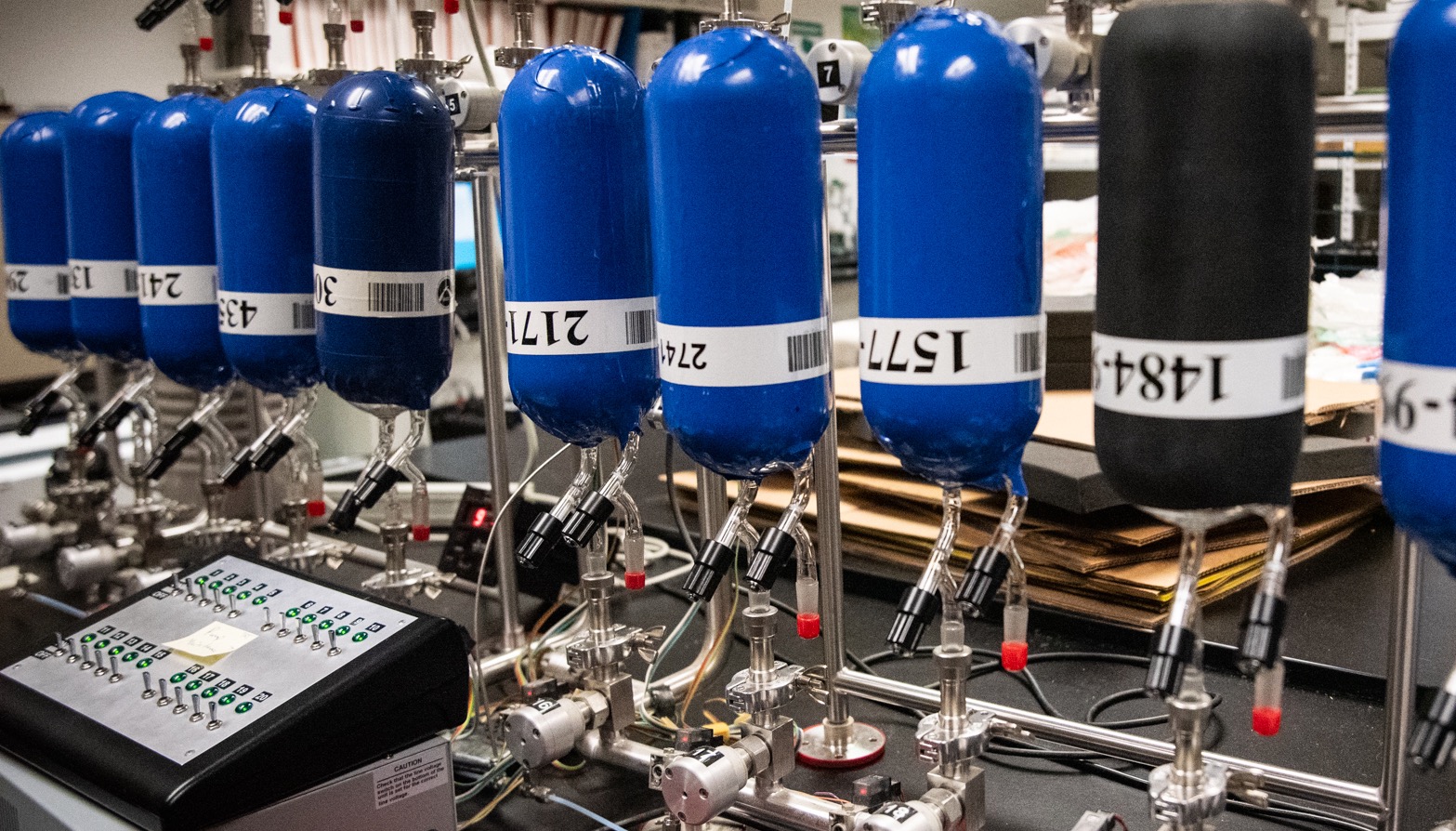

“With HORUS, we now have the unique ability to probe the atmosphere in many under-observed regions, filling critical gaps in our surface observational networks both geographically and in rarely sampled areas of the stratosphere,” said Bianca Baier, a CIRES scientist at the Global Monitoring Laboratory. Baier, the project’s co-lead, has evaluated data collected on HORUS test flights by a payload that included another NOAA innovation, the AirCore, which captures air samples sequentially as it descends through the atmosphere.

With the successful May test, NOAA scientists are looking to bring the HORUS to operational status by spring 2022. The development of the technology is funded by NOAA USRTO and the NOAA Uncrewed Systems Operations Center in the Office of Marine and Aviation Operations.

“The ability to recover high-altitude sensor packages is just one more way that NOAA is applying uncrewed systems technologies to advance scientific research,” said Capt. Phil Hall, director of NOAA’s Uncrewed Systems Operations Center.

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications at theo.stein@noaa.gov, or Xinyi Yeng, NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory at xinyi.yeng@noaa.gov.